Interviews / Europe, European Union, NATO

22 January 2026

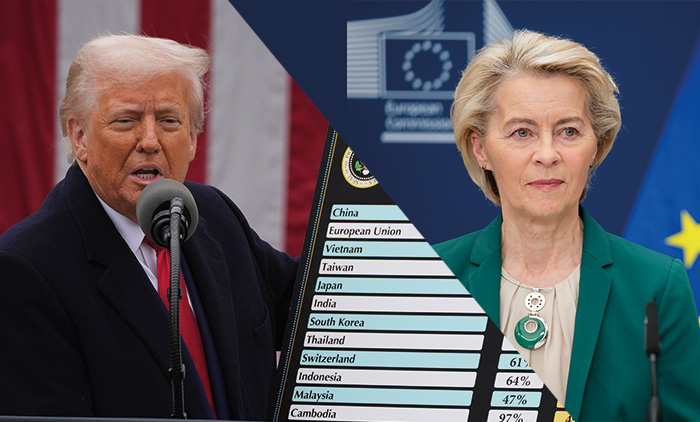

What Responses Can the European Union Offer to Donald Trump’s Trade Aggression?

Even if he declared in Davos that he had (temporarily) backed down, Donald Trump’s announcements threatening certain European countries with a 10 per cent rise in customs tariffs – on top of those stemming from the supposedly ‘reciprocal, fair and balanced’ framework agreement concluded with the European Union in July 2025 – once again place the EU before the dilemma of submitting or responding firmly. What retaliatory tools does it have at its disposal? Has this agreement become obsolete since the European Parliament suspended its ratification process? What would be the impact of new tariffs on trade flows and European growth? The economic risk linked to a firm response is real but should not be overstated, whereas the political risk of submission must not be underestimated. An overview with Pierre Jaillet, Associate Researcher at IRIS and adviser at the Jacques Delors Institute.

Faced with the Trump administration’s aggressive trade policy, what retaliatory tools does the European Union have at its disposal? In particular, the EU’s ‘anti-coercion’ instrument has been mentioned. How and under what conditions can it be activated? Are other actions conceivable, including at national level?

Faced with Donald Trump’s aggressive tariff policy, the European Union is not without means and has a range of legal, trade and diplomatic levers available. Adopted in 2023 (but not used to date), the Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI) is designed in particular to deter and counter the economic pressure exerted by a third country interfering with European political choices (or those of an EU member state). It provides the possibility of applying targeted customs duties to third countries found guilty of ‘coercion’, restricting their access to certain public procurement markets or financial services, blocking their investments in the Union, or even suspending their intellectual property rights. This instrument, sometimes described as a ‘bazooka’, could in reality be applied in a partial and graduated manner. However, it can only be triggered after a relatively long and complex process requiring the agreement of a qualified majority (55 per cent of member states representing 65 per cent of the EU population), which makes its activation fairly uncertain. Nevertheless, it remains a credible option, although it should be considered more as a deterrent capable of rebalancing the EU’s position in the face of Donald Trump’s trade blackmail.

The EU has a few other levers. Admittedly, recourse to WTO litigation procedures (whose fundamental rules – such as the non-discriminatory most-favoured-nation clause – are being openly disregarded by Donald Trump) is currently ineffective due to the paralysis of its Appellate Body. The EU can, in theory, take sector-specific safeguard measures (particularly in the digital field), use anti-dumping instruments or targeted subsidies, and member states retain some control over foreign investment. In practice, the use of these retaliatory measures remains constrained by EU internal market competition rules and the difficulty of building consensus among European countries whose production structures – and therefore their economic and commercial interests – may diverge.

Donald Trump threatened (before backtracking) six EU member states (supported by the United Kingdom and Norway) that opposed his desire to absorb Greenland with a 10 per cent tariff increase (on top of the 15 per cent already in place). The European Parliament also announced that it was suspending the ratification process of the framework agreement concluded between Donald Trump and the EU in July 2025. Has this agreement now become obsolete, and can we expect a firmer EU stance in response to this trade blackmail?

The framework agreement concluded in July 2025 in Turnberry between Ursula von der Leyen and Donald Trump aimed at tariff de-escalation and enhanced cooperation on industrial standards. Although applied provisionally, it required parliamentary ratification. However, the announcement on 20 January 2026 by the European Parliament that it would suspend the ratification process, following the announcement of a cumulative 25 per cent rise in American tariffs (15 per cent + 10 per cent), legally undermines an agreement that has become de facto politically obsolete due to this new unilateral measure. It should be noted that the Turnberry agreement, contrary to the wording of the joint declaration (‘… An agreement on reciprocal, fair and balanced trade’), was in fact neither reciprocal, nor fair, nor balanced, since it endorsed the EU’s acceptance of 15 per cent tariffs (with some sectoral exceptions) on European exports to the United States in ‘exchange’ for the elimination of all tariffs on US exports to the EU, and also included other binding and derogatory clauses for the EU (energy purchases, military equipment, investments in the United States, etc.).

In the (still uncertain) scenario of a renegotiation of this agreement, several signs suggest a firmer stance from the EU. Thus, the six member states (supported by the United Kingdom and Norway) more directly targeted have explicitly rejected any ‘trade blackmail’ linked to American ambitions over Greenland.

Let us bear in mind that the EU accounts for nearly 20 per cent of global GDP and represents a market of nearly 500 million consumers, the largest in the world. Access to it is of vital importance to the United States. But Europeans must collectively adopt a firm attitude towards the aggressor and reinforce their credibility in an assumed balance of power. The risk of escalation naturally exists, and a trade war is always a negative-sum game (especially in a context of highly integrated transatlantic value chains). But the even worse risk is that of a zero-sum game in which Europe would be the sole loser.

What has been the impact so far of rising US tariffs on EU-US trade and European growth? What impact could an additional 10 per cent tariff increase have on the main European economies given their specific specialisations and their respective dependence on the US market?

Since the first US tariff increases, EU-US trade (around €1.1 trillion per year) has slowed. European exports to the United States have fallen by about 5 per cent in volume over twelve months, reducing European growth by around 0.2 percentage points in 2025, according to estimates by the Commission and the ECB. Certain sectors (automotive, machine tools, chemicals, etc.) have been more affected. It should be noted that US importers significantly increased their purchases in the first quarter in anticipation of the application of the tariffs. Overall, the impact is significant but not dramatic, given that gross EU exports to the United States account for only 3 per cent of its GDP. A further 10 per cent increase could, according to some estimates, shave between 0.2 and 0.5 per cent off medium-term European growth (already low at 1.3 per cent in 2026 according to the IMF), with asymmetrical effects (probably twice as large in Germany as in France, for instance), linked to the specialisations of member states’ economies and their level of exposure to the US market. In such an uncertain environment, where increasingly extravagant announcements multiply (such as Donald Trump’s latest threat to apply a 200 per cent tariff increase to French wines and champagne if France does not join the ‘Council of Peace’), one is tempted to recall the aphorism of the humourist Pierre Dac: ‘Predictions are difficult, especially when they concern the future.’ Let us take the reasonable view that a firm and coordinated European response to its aggressor, although involving short-term risks, may reduce long-term uncertainty, to its own benefit and to that of a global economy threatened by fragmentation.