Interviews / Global Health Observatory

21 August 2024

Mpox Virus: A New Public Health Emergency of International Scope That Should Make Us All Sit up and Take Notice

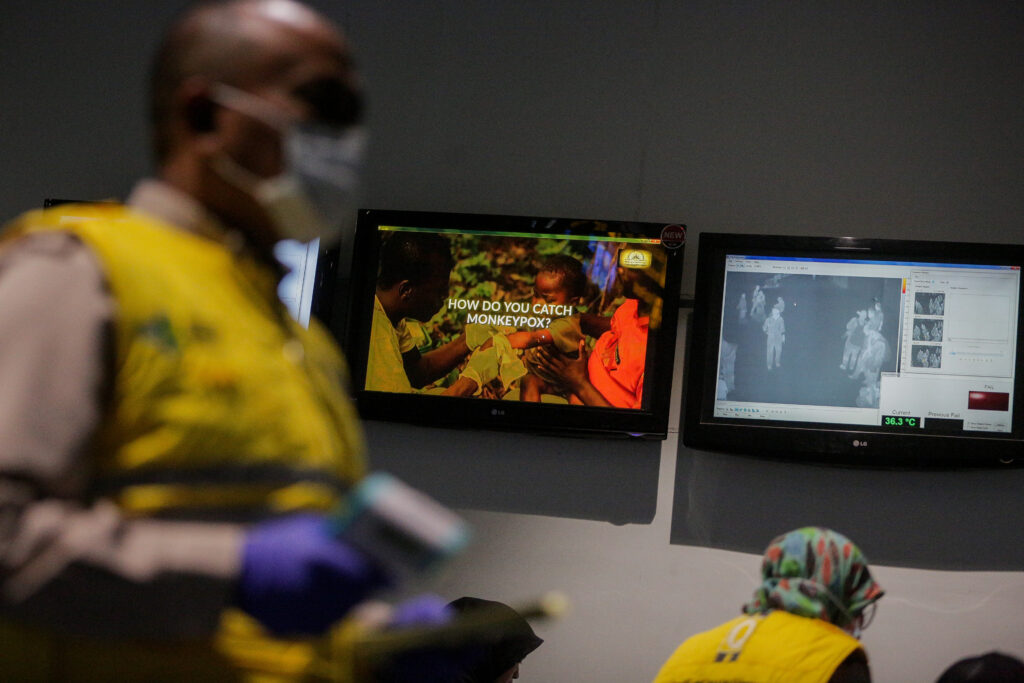

After an initial outbreak in 2022, Mpox, also known as “monkeypox”, is once again spreading, prompting the WHO to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) in order to coordinate international cooperation. What is Mpox, and what is its epidemic potential? What do the increasing number of zoonoses reveal about our practices? An update with Dr Anne Sénéquier, Co-Director of the IRIS Global Health Observatory, who argues that Mpox should prompt a rethink of our public health approach, steering it towards an integrated and cross-cutting strategy aligned with the “One Health” concept.

What is Mpox ?

An emerging zoonosis, Mpox is caused by a DNA virus of the orthopoxvirus genus. Identified in 1958 in Copenhagen, Denmark, in a group of monkeys, it was named “monkeypox”—a misleading and highly stigmatising designation that led the World Health Organization (WHO) to rename it “Mpox” in 2022. This change was all the more necessary given that the natural host of the Mpox virus is in fact a rodent native to equatorial Africa: the Gambian pouched rat or forest squirrels. To date, the animal reservoir has not been definitively identified, but DNA analysis of the virus has revealed multiple transmissions across various forest-dwelling animals.

Mpox causes fever, skin rashes on the face, hands, feet, body and genital areas, as well as headaches, muscle aches, and significant fatigue. Although mild in most cases, complications such as skin superinfections or sepsis may occur in vulnerable individuals (those with weakened immune systems, pregnant women, and young children). The disease can be transmitted through skin contact (via pustules and scabs), sexual contact, and indirectly via contaminated bedding or linens. Airborne transmission via respiratory droplets from an infected person is also possible.

There are two types of Mpox virus : clade 1, originating from the Congo Basin in Central Africa, is associated with more severe symptoms (case fatality rate up to 10 %) and more efficient human-to-human trasmission ; clade 2, from West Africa, has lower mortality rate (under 1 %) and less effective human-to-human transmission.

What is the epidemic potential of Mpox?

In 2022, the outbreak was driven by clade 2b (a variant of clade 2), which, despite the virus’s wide dissemination, maintained a case fatality rate below 1%. The outbreak prompted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) due to the disease’s emergence in 110 countries worldwide.

This year, however, the declaration of a PHEIC concerns Mpox again, but now due to a variant of clade 1, known as “Clade 1b”. This variant carries a higher mortality rate (5–10%) and is more contagious than the 2022 epidemic.

First detected in humans in 1970, Mpox has been endemic (persistently present) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) for the past decade. Since then, the number of cases has risen steadily each year. By mid-2024, there has already been a 160% increase compared to 2023, with 15,600 cases and 537 deaths recorded.

Clade 1b appeared in September 2023 in the northeast of the DRC near Goma, a region plagued by conflict since the mid-1990s. Numerous displaced persons’ camps in the area are already experiencing viral circulation.

By July, 90 cases of “Mpox Clade 1b” had been identified in the four neighbouring countries—Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda—bearing in mind that many other cases likely escaped epidemiological detection. The WHO consequently declared a PHEIC on 14 August.

The declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) enables coordination of international cooperation to contain the outbreak as rapidly as possible. It aims to mobilise actors and partners (Gavi, UNICEF, etc.) to ramp up the vaccination response, by simplifying administrative and logistical procedures to deploy vaccine stockpiles. Vaccination against Mpox is currently carried out using both existing smallpox vaccine reserves and a specific Mpox vaccine that has recently been approved. The WHO has estimated the initial response cost at US$15 million.

Cases have recently been detected on other continents: one in Sweden, another in Pakistan. Given an incubation period of 5 to 21 days, it is very likely that further cases will emerge in the coming days and weeks.

Mpox’s classification within the orthopoxvirus family is both an asset and an added difficulty.

An asset, because it is related to the variola orthopoxvirus (smallpox), which was eradicated in 1980 by a global WHO-led vaccination campaign. As a result, individuals vaccinated against smallpox in childhood are protected, benefiting from cross-immunity: smallpox vaccination offers 85% protection against Mpox and keeps the reproduction rate below 1, which prevented a large-scale epidemic until 2022.

But it is also a difficulty, as smallpox vaccination ceased in the 1980s following its eradication. Consequently, individuals under the age of 40–50 are not vaccinated, which clearly hampers collective immunity. Globally, we now face a reduced level of herd immunity, increasing the epidemic potential.

This, among other factors, explains the growing number of annual cases in the DRC in recent years.

How can Mpox be contained? Why are zoonoses becoming so frequent in recent years?

The frequency of epidemics and their impact on populations have been steadily increasing in recent years. Mpox has moved beyond the fringes of tropical forests, first spreading locally, then into urban areas, from where it has catapulted across the globe.

Since 2018, Mpox has spread from Nigeria (Africa’s most populous country) to the United Kingdom, Israel, the United States, and Singapore, without managing to form clusters.

In 2022, a first global outbreak necessitated raising the alarm: triggering a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC). Between early 2022 and mid-2023 (end of the PHEIC), nearly 90,000 cases were reported, including 147 deaths. And now, in 2024, we are faced with a more transmissible and more virulent variant, released into our increasingly pathogenic globalised world.

Mpox is a zoonosis, a disease of wild fauna that, thanks to increased human interaction, has crossed the species barrier.

This meeting of the wild world and our humanity is driven by massive deforestation and habitat destruction. This phenomenon leads to biodiversity loss, disrupting the dynamics of animal communities. Land-use changes (such as agriculture in forests in search of fertile land), increasing urbanisation, and conflict further aggravate the risks of viral spillover from animals to humans.

In the case of Mpox, this ecosystem degradation caused by human activity must be considered alongside a reduction in cross-immunity, due to the cessation of smallpox vaccination following its eradication.

We thus observe that protecting ourselves from epidemics is not solely a matter of vaccination and PHEIC declarations. Barely four years after the first pandemic of the 21st century, the threat posed by Mpox must prompt us to rethink our public health approach, steering it towards an integrated and cross-sectoral strategy, as embodied in the “One Health” concept. This highlights the interconnection between human health, animal health, and planetary health. We cannot sustain good public health in a world of degraded ecosystems.

To truly protect ourselves from zoonoses (a recurring issue of the 21st century), we must therefore take care of our ecosystems: limit deforestation and intensive agriculture at forest edges; land-use change; halt rampant urbanisation in forest areas; reduce conflict… perhaps idealistic ambitions, but let us not forget that they enable the emergence and/or resurgence of disease (Polio, cholera, Mpox, etc.).

We must therefore change how we act, and ensure that this is accompanied by changes in behaviour and consumption patterns that underpin this ecosystem degradation. A challenge that may seem insurmountable—but do we really have a choice?

Much like climate change compels us to act, the protection of our ecosystems has become just as urgent.

The Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) was created in 2005. First declared in 2009, it has been triggered 8 times over 14 years, with a slight trend towards increasing frequency: H1N1 flu, April 2009 (continuing into 2010); poliovirus, May 2014 (still ongoing); Ebola outbreak in West Africa, August 2014; Zika, February 2016; Ebola outbreak in Kivu (DRC), July 2019; Covid-19, January 2020; Mpox (monkeypox), July 2022; new declaration for Mpox, August 2024…