Interviews / Asia-Pacific

9 September 2025

Indonesia: Anatomy of a Crisis

Since 25 August 2025, only a few days after the celebration of the 80th anniversary of Indonesia’s independence, waves of demonstrations have spread across the archipelago in protest against privileges granted to parts of parliament members [1]. These protests have already resulted in around ten deaths. What triggered this popular uprising? In what context are these demonstrations taking place? How has the Indonesian government responded? An overview with Coline Laroche, analyst at IRIS within the Asia-Pacific Programme, specialising on Indonesia.

What triggered these protests and what are its demands?

These protests stem from long-standing frustrations that had been visible in recent months, particularly on some of the archipelago’s islands around the time of the national holiday. The announcement that members of the House of Representatives (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat – DPR) would be granted a housing allowance proved to be the last straw. This allowance, set at 50 million rupiahs (just over €2,600), was perceived as disproportionate compared to the Indonesian minimum wage, which in 2025 ranges between 2 and 5.4 million rupiahs per month depending on the province. Introduced in September 2024, this allowance came on top of an already long list of existing benefits and high salaries. It caused further outrage because it followed the announcement of new austerity measures by President Prabowo Subianto during the annual session of the People’s Consultative Assembly (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat – MPR) on 15 August 2025.

Initially, the protests were launched by student organisations, workers and trade unions in Jakarta (Java) and Medan (Sumatra) on 25 August. While the mobilisations were relatively calm in the days following the announcement, they escalated on 28 August when 21-year-old motorcycle taxi driver Affan Kurniawan was killed during a delivery after being run over by a police vehicle during a protest in Jakarta. The video of the incident spread across social media, and the fight against police violence was added to the existing anger over inequalities and criticism of a political elite seen as disconnected from the population’s needs. The profile of protesters gradually diversified, and the demonstrations spread throughout the archipelago.

The protests quickly grew in scale due to violent clashes between activists and security forces. On the one hand, numerous attacks and arson incidents targeted symbolic sites such as government buildings, police headquarters, and regional parliaments (in Makassar, Mataram, or Kediri). The homes of some MPs and that of Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati were also looted and vandalised. On the other hand, according to activists and Amnesty International, the police allegedly carried out arbitrary arrests, with Amnesty denouncing “unnecessary and excessive use of force by the police in several cities”.

According to Human Rights Watch, the current toll stands at around ten dead, hundreds injured, and around twenty missing persons. As for infrastructure damage, it is estimated at 900 billion rupiahs (nearly €47 million) according to the Minister of Public Works.

The protests have therefore expanded well beyond their initial economic demands related to the cost of living (raising the minimum wage, tax reform, anti-corruption measures, etc.). They now reflect opposition to police violence, a demand to limit the army’s involvement in civilian affairs, and a broader questioning of the legitimacy and effectiveness of parliamentarians — as evidenced by the widespread #BubarkanDPR (“dissolve the House of Representatives”) hashtag on social media.

These protests are amongst the widest Indonesia has known since the fall of Suharto in 1988 and the start of the Reformasi era, along those in 2019 and 2020. In what economic and political context are these August–September 2025 protests unfolding?

Although these protests are often compared in public debate to the 1998 uprising that overthrew Suharto, such analogies must be treated with caution. They are occurring in a very different context — no longer during the 1997 Asian financial crisis or under Suharto’s dictatorship, but amid persistent economic inequalities and growing distrust of political representatives.

Economically, Indonesia has enjoyed generally favourable conditions since 2014, with annual growth above 5% (except during the 2020–2021 Covid-19 crisis) driven by active development policies, though these have widened inequalities between provinces under Joko Widodo’s presidency. The slowdown at the start of 2025, with growth falling to 4.7% due to an unstable geopolitical and economic environment, is not in itself a rupture. However, it has highlighted entrenched social, economic and territorial inequalities.

Household purchasing power has been weakened by inflation, especially on staple foods (rice, fuel, palm oil, etc.), mass layoffs, and an unemployment rate of 4.76% in February 2025 — affecting mainly young people and above the ASEAN average. Informal work also accounts for 59% of employment, making those workers particularly vulnerable to inflation and insecurity.

Moreover, these inequalities are unlikely to be reduced during the current presidential term due to announced budget cuts affecting infrastructure projects and key sectors such as education and health. These cuts aim to reduce the budget deficit inherited from the previous administration and finance Prabowo Subianto’s flagship (and controversial) programme to provide free nutritious meals to all schoolchildren.

Politically, Indonesians have witnessed a gradual weakening of democracy, which has increased their mistrust of both parliamentary and governmental representatives.

Several factors explain this democratic decline. First, the persistence of political dynasties has perpetuated the same elites. Second, Joko Widodo’s terms saw the weakening of independent institutions such as the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi – KPK), whose autonomy was significantly reduced by the 2019 reform, and the Constitutional Court, whose neutrality was questioned following the 2023 change to the electoral law that allowed Joko Widodo’s son to run for vice-president.

Prabowo Subianto’s rise to power has contributed to a recentralisation of power and a strengthening of the executive, notably by expanding his cabinet and weakening the political opposition, now limited to the PDI-P party. By rallying almost all parties to his coalition immediately after his election, he has secured parliamentary backing. Finally, the recent expansion of the military’s involvement in civilian affairs has raised fears of a possible return of the “dwifungsi” — the dual political and military function of Suharto’s regime.

These factors, combined with corruption scandals, have gradually led to the current protest movement.

This protest movement, the most significant since Prabowo Subianto came to power, represents a major challenge for his administration. What responses has the Indonesian government provided so far, and what room for manoeuvre does civil society still have today?

The Indonesian government initially sought to calm the situation by announcing several concessions, including an investigation into the circumstances of Affan Kurniawan’s death, a reduction in MPs’ salaries, and the removal of certain benefits such as the housing allowance. However, given the scale of the protests and the calls for deep change, these announcements — whose implementation remains uncertain — will likely not be enough to end the unrest, as they address the symptoms of the movement rather than its structural causes: inequalities and institutional mistrust.

Moreover, by describing certain protest actions as “treason and terrorism”, the president has raised fears among civil society of a potential criminalisation of the movement. Given the Indonesian president’s military background, the deployment of the Indonesian army (Tentara Nasional Indonesia – TNI) to support the police during the protests has also revived concerns over the militarisation of law enforcement and the restriction of civil liberties.

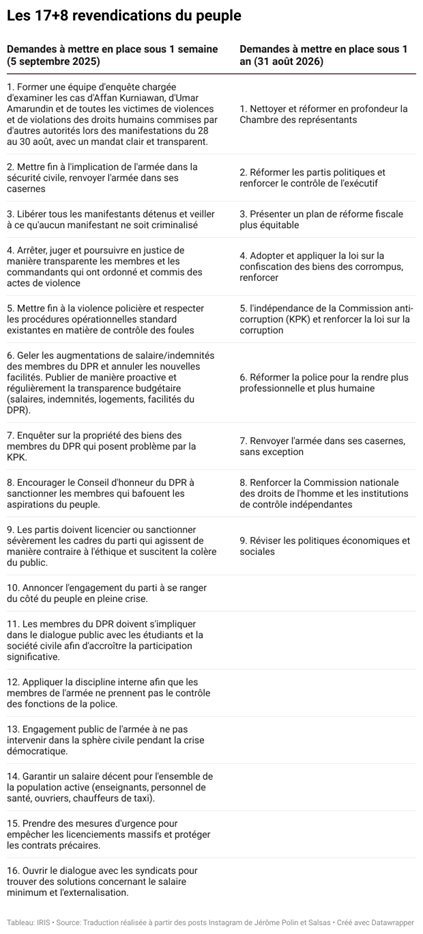

As for civil society, its room for manoeuvre will depend on how the government chooses to respond. Although it quickly organised itself, it initially lacked a clearly identified spokesperson to present shared demands. Since then, the “17+8” movement [2], led by influencers and activists, has published 25 demands on social media addressed to political decision-makers, the military, and the police — some to be implemented within a week and others within a year. If no response is given to the structural issues raised by this wave of protests, demonstrations could continue or resurface later on.

[1] In Indonesia, the Parliament (Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat – MPR) consists of two chambers: the House of Representatives (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat – DPR) and the Regional Representative Council (Dewan Perwakilan Daerah – DPD). Only DPR members are concerned by this allowance.

[2] The “17” refers to the date of Indonesia’s independence, proclaimed on 17 August 1945. The “+8” refers to the number of additional measures added to this symbolic number of 17.