Analyses / Energy and Raw Materials

30 January 2024

Are we heading towards an uranium shortage?

Uranium is the foundation of the nuclear industry. It is thanks to this fissile element that a reactor is able to produce heat and electricity. However, since the beginning of the year, the spot price of uranium has exceeded the symbolic threshold of $100 per pound, after a rise of more than 100% in just one year.

This increase is primarily explained by the renewed interest in nuclear energy, which, according to the International Energy Agency, is expected to play a larger role in the global energy mix, as evidenced by the commitment of 22 countries at COP28 to triple the global nuclear potential by 2050.

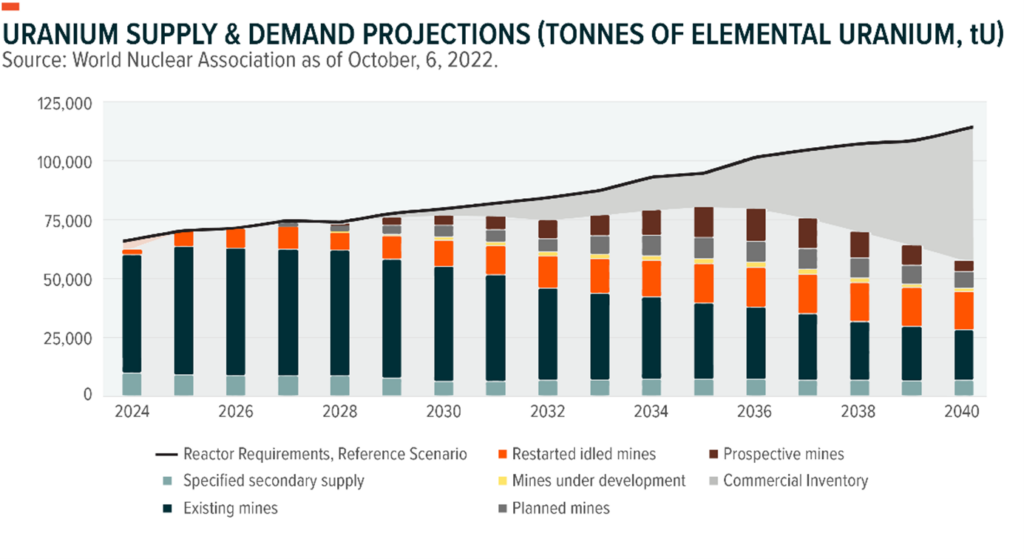

However, this enthusiasm comes at a time when the uranium market could be described as chronically sluggish, with a series of nuclear accidents continually hindering the development of the sector, while the supply of uranium has almost always exceeded demand, due to abundant stocks inherited from the strategic priorities of the Cold War. This imbalance explains why prices have rarely exceeded $80, but few mines can achieve profitability at such low prices. As a result, capacities are now limited, while demand is rapidly increasing and is expected to grow by 27% by 2030.

In this context, geopolitical factors further exacerbate the uncertainty for economic actors, driving up prices. The coup in Niger, the second-largest supplier to the European Union in 2022, naturally fuels concerns. The increasing influence of Russia and China also raises worries. Indeed, both countries have dynamic nuclear industries with high demand for fuel, and they are open about their commercial ambitions, particularly in uranium extraction and value-added processing.

In Kazakhstan, Russia has maintained its influence over extractive activities. Despite Astana’s distancing, the Kremlin retains its stakes in Kazakh mines, which account for more than 40% of global uranium production.

In Namibia, China controls most of the reserves through its state-owned enterprises, CNNC, CNUC, and CGN-URC. As for countries with still under-exploited resources, such as Tanzania and Botswana, the two powers have already positioned themselves to finance future projects. As for Niger, which is determined to redirect its exports to break free from its former partners, China already holds a concession there, and Russia is making diplomatic gestures toward it.

But in addition to these geopolitical and economic factors, other issues come into play, starting with the planned diversification of nuclear technologies, including Small Modular Reactors (SMR), Advanced Modular Reactors (AMR), and Small Nuclear Power Reactors (SNPR), which promise more common, decentralized use and potentially greater uranium consumption. These prospects also raise questions about the nuclear industry’s ability, by nature concentrated and heavily regulated, to adapt to this complex energy landscape.

However, there is no crisis, and even less a uranium shortage on the horizon. While there has been a price increase, it will have little impact on the final price of nuclear electricity, as the fuel’s share is minimal and secured by national stocks and long-term contracts. On the contrary, the rise in prices allows for the reopening of operations that were previously closed due to lack of profitability. This is the case in Namibia (Langer Heinrich), Canada (McClean Lake), the United States (Christensen Ranch), and Malawi (Kayelekera).

It is also wrong to accuse China and Russia of trying to strangle Western nuclear capabilities. Not only do they lack the means to do so, but their primary interests lie in meeting their own needs and enhancing their attractiveness in an expanding market, where Western countries are not the only ones engaging. Furthermore, it is incorrect to speak of a Sino-Russian axis when the two countries are clearly competing for mineral acquisition and the export of their own nuclear technologies.

If there is to be a uranium crisis, it is not imminent. However, this heating up of the markets reminds us that nuclear power, like any energy source, relies on raw materials and, by extension, imports that can be sources of vulnerability. This is an oversight, especially in France, where uranium supplies are still not accounted for in the country’s energy independence rate.

________________________

Complementary sources :

World Nuclear Association, « Uranium Markets », juillet 2023.

OEC, « Fuel elements non-irradiated, for nuclear reactors », 2023.