11.10.2024

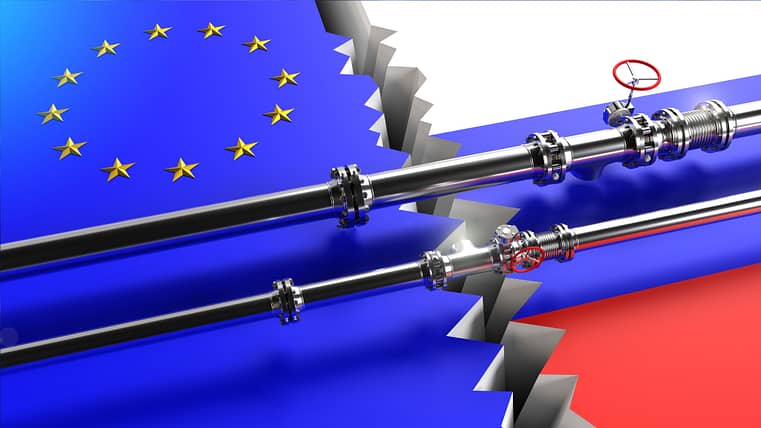

Failing to Diversify Gas: Europe’s Decades-Long Renouncement Toward Russia

Tribune

3 mars 2022

The failure to diversify natural gas sources leaves Europe without a convincing solution to such a premeditated Russian invasion of Ukraine. We find ourselves playing poker against chess players. Europe imports more than a third of its natural gas from Russia, and has given up most of its strategic leeway in this sector. Even though Europe’s political rhetoric was intended to be increasingly firm toward Russia, particularly with the idea of NATO expansion, in reality our dependence on Russia has increased year after year. This gap is exemplified by the major German-Russian agreements around Nord Stream 1, opened in 2011, then Nord Stream 2, just suspended before going into operation. The major diversification routes that Europe had been planning for since the early 2000s have been abandoned or reduced to a fraction of their original scope. The idea of a Southern Corridor from the Azeri Caspian fields as an alternative has been replaced by a gigantic northern, maritime route bypassing Ukraine, directly from Russia to Germany.

Turning Germany into a Major Hub for Russian Gas… and Bypassing Ukraine

In Germany, the share of gas imports from Russia is estimated at nearly half. The relative weight of Russian gas imports can vary significantly from one year to the next, and from one month to the next, but the trend has clearly been upwards over the last ten years, by more than 20% in Europe, while Norwegian production was beginning to stagnate overall. With Nord Stream 2, Germany’s dependence could have reached 70%. Nord Stream 1 has an annual capacity of 55 billion cubic meters (bcm). Nord Stream 2 was to double this capacity. 110 bcm is more than all of Germany’s natural gas consumption (about 100 bcm)! At the same time, the country has strongly developed its storage capacities. The aim was clearly to turn it into a major import-export platform for Russian natural gas, in addition to guaranteeing the country’s energy security after the end of nuclear power and satisfying Russian requirements to bypass Ukraine.

The Southern Corridor: A Missed Opportunity for Diversification

Alternative projects developed under the Southern Corridor framework were rightly presented as major diversification initiatives for Europe from the early 2000s until just under a decade ago. European countries, like Italy, Greece or Austria, each projected themselves, depending on the route options, as the hub of this southern route for distribution to the rest of Europe or at least its southern half.

On the one hand, Nord Stream, this gigantic northern route, has taken its place. On the other hand, while gas from the Azeri fields in the Caspian remained an alternative, the various secondary branches to Iran and Iraq have obviously disappeared in the wake of political ruptures and security crises. It would not be surprising, however, if a new commitment to diversification quickly led to improved relations with gas giant Iran and to new agreements.

In the end, instead of a major diversification route for Europe, the Caspian gas route has only into developed a modest interlocking of much smaller projects in Azerbaijan and Turkey, in particular, to Europe.

Russia has sought to bypass Ukraine for a long time. Already in the days of pro-Russian Yanukovych, there were incessant disputes about the fees charged by Ukraine and even more about the share of gas taken, with Moscow regularly accusing Kiev of siphoning off Russian gas flows to Europe. While various diversification projects were on the table in Europe, this Russian plan to bypass Ukraine resonated with the German objective of guaranteeing direct access to Russian gas, even if this meant considerably weakening Ukraine.

Energy Diversification Would Have Been More Effective than Banking Sanctions

This long drift has resulted in a loss of strategic room for maneuver. We therefore have to focus on financial sanctions with international repercussions that are difficult to anticipate and contain, such as banning some Russian banks from the SWIFT protocol. This type of measures was designed for Iran, which was already much less inserted in world trade. Above all, these measures of financial blockade were accompanied by the equivalent isolation in trade, and energy in particular. With heavy financial sanctions against Russia, there are still channels left, if only to be able to pay for our gas imports and receive payments from Russia. These sanctions are massive as such, but because of the extent of the dependence on energy flows, they are necessarily fragmented and unevenly applied.

The alternatives are limited in the short term. Liquefied natural gas is one of them, already accounting for slightly more than a quarter of European imports. However, the infrastructure is still quite limited, and non-existent in Germany, for example, which relies on the infrastructure of neighboring Netherlands. These take less time to build than large gas pipelines, of course, but they cannot be erected overnight. Flexible US supply has helped to increase European LNG imports. However, it is extremely difficult to overcome a tendency towards ultra-dependence in gas pipeline imports, which has developed over decades, since the days of the USSR, following long-term contracts with often opaque financial commitments. It should also be noted that Russia still accounts for 20% of the LNG imported by Europe, just behind the 26% share of the United States and 24% of Qatar…

This piece has initially been published as an interview by Atlantico in French.