25.07.2024

The IOC Won’t Take a Knee: On the Rule 50, Protest Politics and (A)political Games

Tribune

30 avril 2021

On April 21, 2021, the Athletes’ Commission (AC) of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) published a set of recommendations on the Olympic Chart’s Rule 50, concluding that the rule should be “restructured” but ultimately maintained. The AC’s final recommendations, already endorsed by the IOC’s executive board, were eagerly expected as the consultation process began in June 2020 as a response to the recent surge of athlete activism.

As many athletes across the world were kneeling down as a sign of protest for social justice, the IOC’s Rule 50 – which prohibits any kind of political, religious or racial demonstrations on all Olympic sites – was particularly scrutinized as other major sports governing bodies such as the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) or the National Football League started implementing measures tolerating protest on the field.

Based on the AC’s recommendations, it is now confirmed that the IOC won’t follow the trend. The set of recommendations does concede to some forms of “athletes’ expression” in the Olympic Village or through athlete apparel, although it remains unclear whether all sorts of expressions will be tolerated.

As of the podium, field of play and official ceremonies, the AC recommended that they shall be preserved, hence confirming their support to the core of the Rule 50. It is then confirmed that protests – such as taking a knee – will be prohibited during the upcoming Olympic Games in Tokyo this summer and the 2022 Games in Beijing. The report, to justify the AC’s support of the prohibition, cites a quantitative study conducted by Publicis Sport & Entertainment and contracted by the IOC as context.

Some limits in the quantitative study’s representation of athletes

The Publicis study found that 67% of the 3,547 surveyed athletes supported a ban on podium protests, and that 70% were opposed to protest during both field of play and official ceremonies. The fact that the AC apparently heavily relied on this quantitative study is problematic.

Firstly, 3,547 seems to be a relatively small number when, in comparison, 11,091 athletes are expected to perform during the upcoming Tokyo Summer Olympics, and 4,400 in the Paralympics. As of the 2018 Winter Games, a total of 2,922 athletes participated. Within the sample, the two most represented sports were “Aquatics” and “Athletics” with 12% of surveyed athletes performing in the first discipline and another 12% in the second, as well as “Other sports” accounting for 28% of the sample. As athlete activism widely varies across sports disciplines, the disparity in represented athletes by sports constitutes a problem – however relatively minor – of representation.

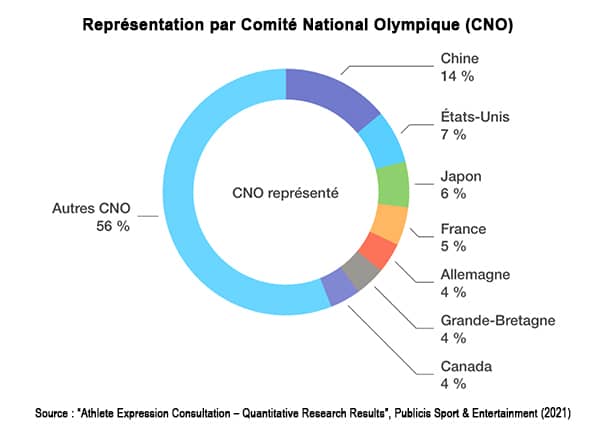

Another issue in the survey’s sample stems from disparities in national representations. The most represented National Olympic Committee (NOC) is China’s with 14% of surveyed athletes. The American NOC comes second, with only 7% of athletes, meaning that there were twice more Chinese athletes than American athletes represented in the sample.

Figure 1: Representation of National Olympic Committees (NOCs)

Source: “Athlete Expression Consultation – Quantitative Research Results”, Publicis Sport & Entertainment (2021)

This disparity is important because the Publicis report reveals strong national trends, with the NOCs of China and Russia being largely opposed to sharing their political views publicly while that of the United States, Canada, Germany and Great Britain often find themselves at the other end of the spectrum, tending to support such politicized behaviors. For example, 87% of surveyed athletes from the Chinese NOC and 56% from the Russian NOC were against expressing their individual views on political issues at press conferences, against less than 30% opposed among the aforementioned Western countries. Those strong correlations between country of origin and opinion suggest that the sample should have attempted to be more equally distributed across countries for a fairer representation of views.

Figure 2: Athletes by NOCs opposing opportunities to express their individual views during ‘Press Conferences’

Source: “Athlete Expression Consultation – Quantitative Research Results”, Publicis Sport & Entertainment (2021)

Even if all countries were represented equally, it is likely that opposition against political protest during the Games would have remained prominent. One of the first questions illustrated in the Publicis report found that half (49%) of athletes “never” demonstrate their views publicly while nearly 1 out of 4 (22%) “never” even demonstrate their views privately. Such low level of politicization among athletes – which should not be perceived as problematic in itself, as athletes have the right not to engage with politics – obviously led to the striking statistics of more than 2 out of 3 athletes opposing politicized behaviors during the Games more generally.

Figure 3: Percentage of athletes across all NOCs who express their views publicly and privately

Source: “Athlete Expression Consultation – Quantitative Research Results”, Publicis Sport & Entertainment (2021)

Source: “Athlete Expression Consultation – Quantitative Research Results”, Publicis Sport & Entertainment (2021)

Protest politics as “weapons of the weak”, not the majority

However, beyond those details which partially explain why the findings largely advantaged protest opposition, the use of a quantitative survey to justify the maintaining of a ban on political protest by the AC is problematic in itself.

Protest is a form of public expression which usually aims at changing society’s power structures, hence often provoking vivid opposition by parts of the population. For example, the podium protest of Tommie Smith and John Carlos during the Mexico Olympics in 1968, now widely praised, was initially largely decried by the majority of Americans. Indeed, efforts by Black American athletes to denounce racial injustice through the 1960s were met with backlash and opposition all along the way. It is now remembered as the most powerful protest gesture in US sport history, but athlete activism still remains a polarizing issue.

The field of sociology is very interested in protest and social movements, which it describes as the “weapon of the weak” and forms of resistance used by those who don’t have enough leverage otherwise to participate in “traditional” politics. Protest is, in other words, meant to provide a platform and bring about social change for those who traditionally don’t have a voice in society. As protest often aims to give power to the minority and/or the disadvantaged, it is largely expected that the majority/privileged – which tends to accept a status quo which advantages them – will be mostly represented in quantitative studies such as the Publicis report.

The “apolitical Games” fantasy continues

It is therefore very irrelevant for the AC to justify the maintaining of the ban on podium protest through the citing of a quantitative study which was obviously going to represent the majority of athletes – some of whom have never been allowed to express themselves freely in their country and with very different protest cultures and regulations – against a socio-political practice of unconventional politics often used by the underrepresented.

Taking this a step further, the very foundation on which the IOC has opposed athlete activism in the first place is flawed, hence explaining why many of the justifications ensuing are also problematic. Again, the AC’s recommendations were drafted around the core aim of protecting the “neutrality” of Olympism, a pillar to the sports movement. The Olympic Games however, sports history studies show, have never been politically neutral. The mega-sporting event has been largely politicized, notably by the host countries and particularly since sport became a proper tool of soft power.

If the IOC wanted to have completely apolitical Games, it would, for example, sanction the Tokyo Organizing Committee for branding itself as the most gender-balanced or as the most innovative Olympic Games in history as it aims to share a modern and inclusive image of Japan to the world. The fact that it won’t, in addition to its deep commitment to a principle that has never been truly implemented during any Olympic Games, highlights very deep inequalities laying at the heart of the Olympic movement’s power structures – with athletes, as always, being left at the very bottom.

—————–

This article belongs to the GeoSport platform, developed by IRIS and EM Lyon.