Analyses / Latin American/Caribbean

2 September 2024

X Blocked In Brazil: A New Episode in the Power Struggle Between States and Digital Multinationals.

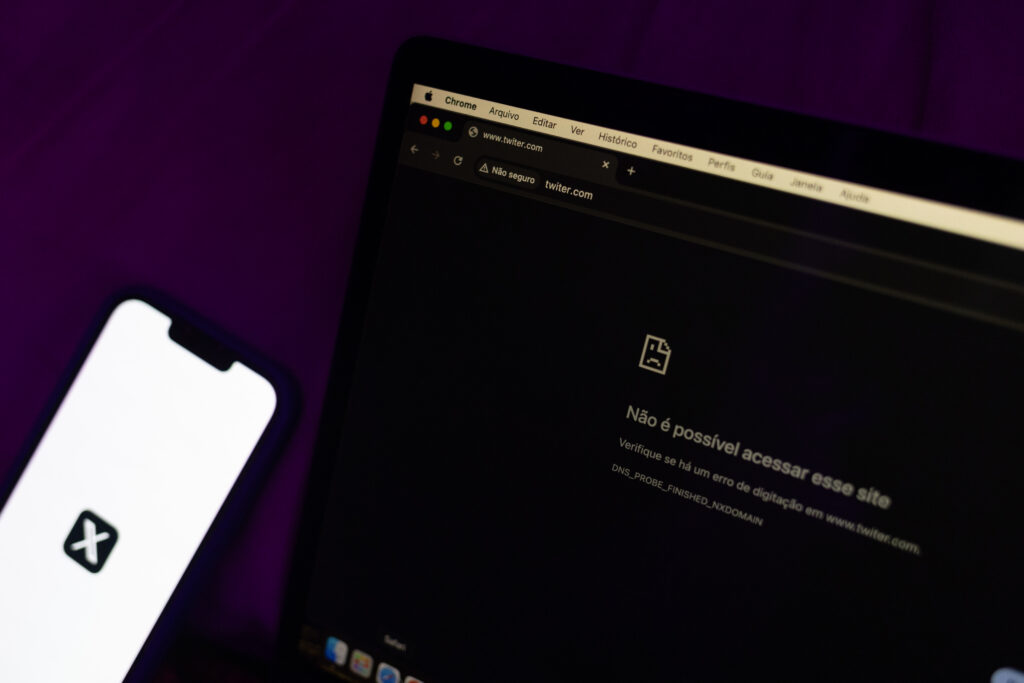

With the suspension of X, the Brazilian judiciary asserts the sovereignty of the state in the digital space and raises, once again, the question of the power of multinationals over public institutions.

By deciding to suspend the social network X (formerly Twitter) in Brazil, the judge of the Federal Supreme Court (Brazil’s equivalent of the Court of Cassation and the Constitutional Council combined) brings back to the forefront the critical question of the power of digital multinationals over states.

The terms of the conflict are rather simple. The platform did not comply with the judge’s orders. The latter requested the removal of certain user accounts linked to the riots by supporters of Jair Bolsonaro targeting public institutions in the Brazilian capital on January 8, 2023. However, instead of submitting to the supreme court’s orders, the owner of X, Elon Musk, invoked the principle of “freedom of speech” to avoid fulfilling his obligations. Condemned to pay a daily fine of 200,000 reais (around 32,000 euros), X chose to ignore this penalty and did not pay the fine. Moreover, the platform decided to no longer have a legal representative in Brazil: a final infraction that convinced the supreme court judge to block X in Brazil.

In this case, two main issues can be identified. The first is the ability of a state to maintain order (social order) in the digital space, especially when seditious impulses and attempts at a coup are partly being fostered from social media platforms. The Brazilian state seeks to ensure the effectiveness of its sovereign functions both online and offline, and to transpose the principle of sovereignty into the digital space. The second issue concerns the adaptations that a foreign multinational is willing to make to secure sustained (and unobstructed) access to a national market. Indeed, economic power is not everything. There is a set of legal, social, and symbolic norms that a company must respect to be accepted as a legitimate actor in a country’s economic landscape where it has commercial ambitions.

On this last point, it is important to emphasize that the internet has never been the so-called “Wild West” so often criticized by governments worldwide since the 1990s. States have always had control over the Network, with applicable laws enforced, sanctions, access restrictions, and site and application blocks. These measures can cause collateral damage: blocking an IP address not only prevents access to a specific site but also to other content hosted on the server answering to that address. Furthermore, workarounds exist, such as VPNs – although Brazilian users risk a fine (8,000 euros) for using such services to try to access the platform.

Other companies have also played the leverage game with public authorities in the past. This has been the case in Brazil with the Telegram messaging service (whose founder, Pavel Dourov, was recently arrested in Paris), which was temporarily suspended in 2022 and 2023. It is also true in France, where, for years, a company like Google refused to comply with public authority orders, such as those from the CNIL in 2014 or the Competition Authority more recently.

However, a blocking case like that of X in Brazil is extremely rare in Western democracies. In many ways, these companies have put states in a position of dependency. Not least because they form an oligopoly and largely control access to the digital space. Few states have developed the capacity for independent intervention on networks, and many of them must rely on these multinationals to make their online power effective.

On the other hand, these firms (like any company) are dependent on states in several respects. As Max Weber puts it: “Capitalism requires bureaucracy.”[1] Telecommunications networks, on the one hand, are still largely under state control, through public enterprises or national companies that are much more controllable than multinationals based on the west coast of the United States. Moreover, to use Pierre Bourdieu’s words, the state functions as a “central bank of symbolic capital”[2]; in other words, it is through the state that the reputation of companies is forged, rules are set for them to appear as legitimate actors, and, consequently, they protect themselves from hostile mobilizations, regulations, and sanctions by public authorities.

However, the major issue of our time is this “asymmetric interdependence”[3] which seems to tilt in favor of the digital multinationals. To take the previous examples, these companies have found ways to bypass national telecommunications networks. This is true for Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon, in particular, which have played a major role in the deployment of intercontinental communication cables in recent years. This is especially true for the economic empire being built by Elon Musk, with his company Starlink opening satellite-based internet access – at the risk of depriving states of that fundamental attribute of sovereignty: control over communications within their territory.

Additionally, we cannot ignore the fascination these companies exert on governments in many countries. In fact, digital technology is often presented as the ultimate solution for economies operating at a slow pace, plagued by mass unemployment, a declining demographic, but also insurgent tensions that pique the interest of states in these technologies, which are easily used for social regulation purposes. One only has to see the honors bestowed upon the leaders of these companies when they are received by heads of state and government in the West, with the reverence usually reserved for foreign rulers and diplomats. The financial, technological, and symbolic capital of these multinationals is highly sought after. Through this capital seems to be at stake, paradoxically, not only the capacity of states to act, but also the political credit of leaders who must prove they still have a grasp on reality when everything seems to demonstrate their powerlessness.

[1] Max Weber, Économie et société, t. 1, Les catégories de la sociologie, Paris, Plon, 1971.

[2] Pierre Bourdieu, Sur l’État. Cours au Collège de France (1989-1992), Paris, Raisons d’agir/Seuil, 2012.

[3] Marlène Benquet, Fabien Foureault, and Paul-Lagneau Ymonet, “Coproduire la règle du jeu. État, assurance, et capital-investissement dans la France des années 1990,” Revue française de sociologie, vol. 61, no. 1, 2020, p. 79-108. du jeu. État, assurance et capital-investissement dans la France des années 1990 », Revue française de sociologie, vol. 61, n°1, 2020, p. 79-108.