Analyses

3 March 2025

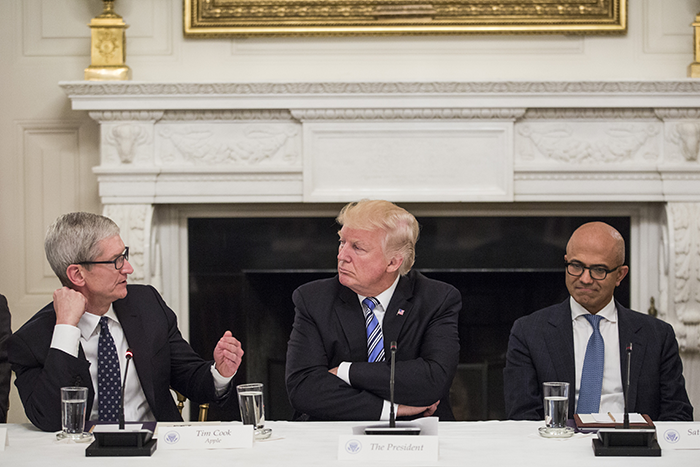

When Trump defends his GAFAM

On 21 February 2025, the President of the United States signed a memorandum entitled “Defending American Companies and Innovators from Overseas Extortion and Unfair Fines and Penalties.” It is based on the premise that U.S. digital companies have been targeted by “extraterritorial” measures that hinder their economic expansion, to the detriment of the “Nation’s well-being,” American sovereignty, and jobs.

The memorandum traces what is presented as an unjustified aggression back to 2019. At the heart of the issue is a half-dozen countries—France, Austria, Italy, Spain, Turkey, and the United Kingdom—that introduced specific digital sector taxes. These states are accused of having legislated discriminatorily and disproportionately against U.S. firms to transfer substantial funds or intellectual property from American companies to their governments or state-backed national entities. In response, Donald Trump announced that his administration would retaliate with tariffs and “all necessary measures to mitigate the harm caused to the United States.”

Indeed, in 2019, the introduction of the digital services tax (dubbed the GAFA tax) by the French government provoked the wrath of the first Trump administration, leading to threats and retaliatory measures of the same kind, including tariff increases, particularly on luxury goods. As a result, the French Ministry of Finance quickly asserted that the tax would be only temporary, pending an agreement among OECD member states on multinational taxation.

As its name suggests, this tax specifically targeted U.S. digital multinationals. It was only as a legal precaution, to avoid the risk of being deemed unconstitutional, that the Finance Ministry and its advisers agreed to expand the tax’s scope so that some French companies would also be subject to it, thus avoiding accusations of discrimination. This decision frustrated French companies, such as Criteo at the time.

However, taxation is not the only issue at stake. The memorandum also targets, more broadly, “regulations” adopted by certain foreign governments, primarily EU member states and the European Union as a whole. A close reading of the memorandum makes it clear that the U.S. administration has in mind European laws enacted over the past decade, including the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR[1]), the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and its counterpart, the Digital Services Act (DSA), the Gigabit Infrastructure Act, and the Artificial Intelligence Act, which came into effect in early February 2025. It is evident that the DSA and its British equivalent, the Online Safety Act, are singled out in section 3(d) of the memorandum: any measures taken to “undermine freedom of expression, political activism” are being targeted by the United States. It is also no coincidence that one of Donald Trump’s closest advisers, Elon Musk, president of X (formerly Twitter), is also one of the fiercest opponents of online content regulation measures—invoking a rather flexible interpretation of “freedom of expression,” to say the least.

More broadly, any initiative that could “undermine the global competitiveness of U.S. companies” is now subject to retaliation. The particularly vague wording of this statement suggests that the United States expects other countries to remain entirely passive in the face of the expansion of GAFAM companies, which now enjoy a blank cheque from the Trump administration to extend their activities without any legal or other constraints.

No one will be surprised that, despite the diversity of issues it addresses, the memorandum formalises the nationalist policy of the U.S. president. Nor should it be surprising that this policy manifests itself so clearly in the digital technology sector. The United States has built its technological dominance on a nationalist and even interventionist policy in the computing and digital economy sectors. It is no coincidence that, in the 1960s, American economist John Kenneth Galbraith described the U.S. economy as a “managed economy”—a standardised system of deep ties between the high-tech industry and the state, which he called the “technostructure.”

Some keen observers of European legal and technological policy may question such an aggressive stance from the U.S. president. In reality, Europeans have so far not been particularly combative towards U.S. digital multinationals. On the contrary, every regulatory move is carefully considered to avoid hampering innovation—a political mantra of recent years, which, in practice, means ensuring that any significant technology firm, particularly American ones, is not obstructed. Even the measure that seems to irritate the Trump administration the most, the “GAFA tax,” was developed—or rather co-developed—in close collaboration with the lobbying representatives of these very companies. Amendments were even discreetly introduced in the French Senate at the request of the finance minister’s office to accommodate the demands of certain firms.

More generally, despite the real proliferation of regulatory measures and the hostile rhetoric of European leaders toward GAFAM, Europe’s stance has always been to do its utmost to attract their financial and technological investments. As recently as 2023, the European Commission worked to smooth over the “insult” of the 2020 European Court of Justice ruling that deemed the transfer of Europeans’ personal data between the EU and the U.S. illegal. In response, the Commission rushed to adopt a new “adequacy decision” recognising U.S. legislation as compliant with the GDPR—leading to the establishment of the Data Privacy Framework in July 2023—which once again allowed these transfers until a likely future invalidation by the same court.

A natural reaction would be to attribute these political and bureaucratic stances to the powerful lobbying of GAFAM. It is true that these companies are among the biggest spenders in this area, both at the national and European levels. Meta, Microsoft, Apple, and Google are indeed among the top 15 organisations in terms of lobbying budgets, according to the EU transparency register. However, their institutional influence is relatively modest compared to large national and European corporations, which have maintained close relationships with national and EU political and bureaucratic circles for years, if not decades. If European firms were pushing for a more confrontational approach towards GAFAM, they would likely find a receptive audience. However, so far, Europe’s largest companies have been among the staunchest defenders of American digital multinationals. Major French business organisations, for example, played a key role in diluting France’s “sovereign cloud” policy—to the extent that French ministers explicitly encouraged the adoption of Microsoft and Google technologies. Some French professional organisations were also at the forefront of efforts to prevent the GAFA tax, which they saw as driving up the costs of American firms’ services, particularly their advertising platforms.

In reality, U.S. multinationals have established such a gravitational pull in the European (and global) economic landscape, and their digital technologies play such a critical role in structuring international economic power dynamics, that any policy or administrative measure that might slow the flow of their financial and technological capital into the European or French production system is perceived as a threat. What would happen if Amazon Web Services (AWS) or Microsoft Azure cloud services became unavailable or prohibitively expensive? How could advertising campaigns be conducted without the support (or preferential rates) of major platforms like Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube (Google)? And how could businesses expect substantial productivity gains from artificial intelligence without the contribution of the U.S. private sector, the world’s largest investor in AI, with $62.5 billion spent in 2023 alone?

It is clear that relations between European and American multinationals have been built on a web of deeply asymmetric interdependencies, overwhelmingly in favour of the latter. This dependency now raises a crucial question: will Europe’s major corporations support or oppose stricter regulatory policies on GAFAM? Until now, they have been eager to protect the interests of their American counterparts. The question remains whether the Trump administration’s unbridled nationalism will be enough to change their minds.

[1] The memorandum targets “foreign legal regimes [that] restrict cross-border data flows,” which is the case with the GDPR.