Analyses / Asia-Pacific

2 October 2025

Tokyo and Seoul: Rethinking security beyond the United States?

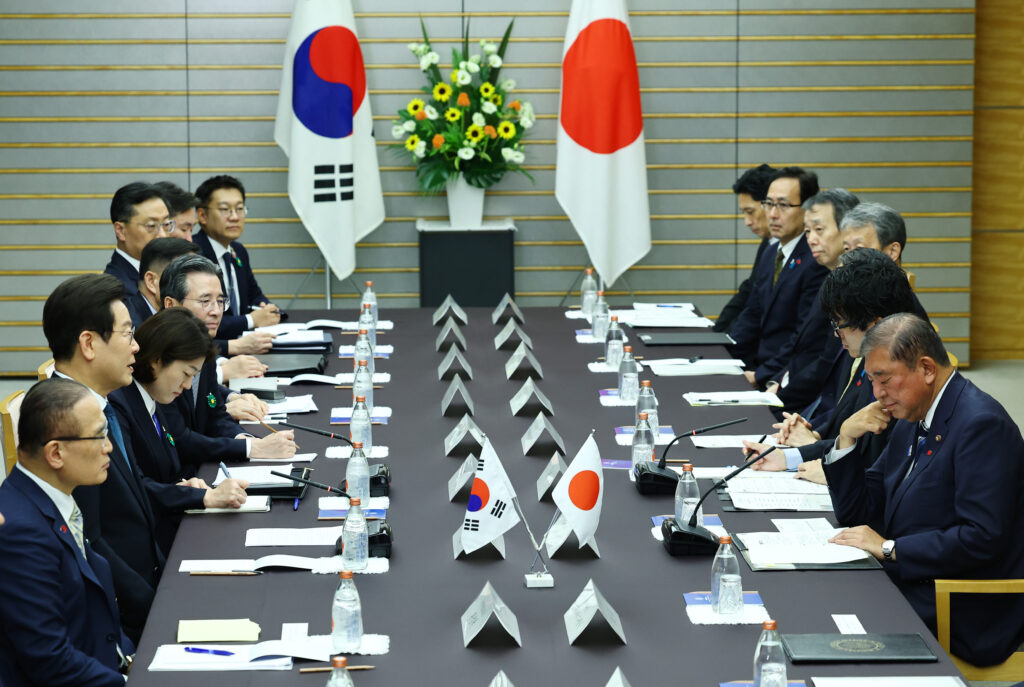

On 3 September 2025, the summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation proudly showcased the presence of the leaders of India, North Korea and Russia alongside the Chinese president. The following day, as he displayed China’s military strength in a parade commemorating the end of the Pacific War, Xi Jinping took the opportunity to reflect on the transformations of the international scene and the need to reform its governance. His speech, combined with the display of solidarity among the four autocrats, heightened alarm in both Seoul and Tokyo, already unsettled by the mutual defence treaty signed between Russia and North Korea in June 2024. If a world order underpinned by revisionist states is not the future envisaged by the two liberal democracies of East Asia, their political and military ties with the United States and the future of the security treaties binding them to Washington nevertheless remain deeply concerning.

The level of tariffs and the rising costs of maintaining the military alliance with an unpredictable and transactional Donald Trump are becoming increasingly burdensome. In the long run, these combined pressures could have very negative repercussions on the political, economic and financial stability of both Japan and South Korea. The course of Trump’s first year back in office already signals a difficult future for the two most faithful Asian allies of the United States.

American demands weakening the Japanese and South Korean governments

In the months ahead, one may wonder how Japanese and South Korean consumers will react to the tariff hikes imposed by the United States, particularly domestic industries such as the automotive sector, which has been especially hard hit. The car industry is a major employer in both Seoul and Tokyo. In 2024, the automotive sector generated 34.7 billion dollars for South Korea, nearly half of the country’s total exports. The fact that tariff negotiations were coupled with investment agreements added another layer of complexity to an already highly imbalanced politico-economic dialogue with Washington. For example, Japan committed to investing 550 billion dollars in new projects in the United States. South Korea, for its part, must invest 350 million dollars in the United States – including 150 million in shipbuilding – while also importing 100 billion dollars of American energy products.

Donald Trump’s transactional logic points to arduous discussions ahead over the financial aspects of alliance management, another sensitive issue for Japanese and South Korean public opinion. The US president has repeatedly insisted that his Asian allies (like the Europeans) do not pay enough for their security. Yet further financial demands will be difficult for Tokyo and Seoul to handle. Their governments are forced to navigate between the centrality of the US relationship, the vagaries of their own domestic politics, and the discontent of their citizens. Already, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba’s difficulties in negotiating American tariffs have cost him his job, especially as his popularity had already been waning since the July 2025 legislative elections, which saw the decline of the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). His resignation and the LDP’s erosion likely herald a period of political instability in Japan, while a nascent populist movement has now gained institutional representation with the ultraconservative Sanseito party’s entry into the Senate.

Renewed frictions over the cost of security alliances

Signs of mounting pressure are already visible between Washington and its two partners on defence and military cooperation, with Tokyo and Seoul left with little room to argue. While the bilateral security treaty with Japan does not include military reciprocity, it does require the archipelago to provide bases and facilities for US forces. It may be time to remind Donald Trump that without these bases, neither the US Navy nor Air Force would be able to intervene rapidly and effectively in a regional crisis. The port and air facilities used by the United States in Japan and South Korea are essential to respond to any regional emergency scenario – whether on the Korean Peninsula, in the Taiwan Strait or in the South China Sea. Still, Tokyo and Seoul are being asked to do more. US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has already argued that Indo-Pacific allies must meet the same spending levels as NATO members – 5% of GDP. Yet South Korea already devotes 2.8% of its GDP to defence, while Japan allocates 1.8% and aims for 2% by 2030.

In the coming months, Washington and Tokyo must renegotiate the five-year agreement defining Japan’s financial support for the US military presence on its soil. Japan’s contribution currently stands at 2 billion dollars per year, but during his first term Donald Trump floated the figure of 8 billion annually. With the archipelago mired in political turbulence, it hardly seems in a position of strength for such talks.

Similarly, in 2024 South Korea and the United States signed a new five-year agreement on cost-sharing for the stationing of 28,500 US troops in the country, primarily as a deterrent against North Korean aggression. Seoul agreed to increase its contribution by 8.3%, reaching nearly 1.174 billion dollars. Although this agreement remains in force, further admonitions from Washington are to be expected. South Korea remains committed to the alliance, as shown by its rising financial contributions and its fear of any reduction in US forces – but how far will it go?

It would appear that America’s two closest Asian allies are now being cornered into political and military choices they have long postponed, concerning the gradual acquisition of more autonomous deterrent capabilities – capabilities their respective defence industries are in a position to design and build. In both Tokyo and Seoul, without renouncing an alliance that remains indispensable, it is now necessary to consider strengthening national strategic means, playing a greater role in regional coalitions and frameworks (QUAD, “AUKUS plus”), extra-regional ones (EU, NATO), and modernising their defence apparatus technologically, including with new industrial partners. Both countries, already able to provide substantial direct military support to Ukraine, could find cross-technology partnerships with European industries mutually very beneficial.