Analyses / Europe, European Union, NATO

6 May 2025

Stepping Up a Gear: Towards a European Strategic Mobility Agency

The term “military mobility” has long emerged, both within the European Union (EU) and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)[1], as the area of action intended to enable the rapid and large-scale movement of armed forces. The policies developed in this domain are mainly focused on the European continent, but it is also recognised – particularly within the EU – that such mobility should support operations conducted under the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) and thus apply wherever the Union’s security interests are at stake.

Numerous initiatives have already been launched in this context, yet significant difficulties are still reported by military personnel moving across Europe. In terms of capability development, these difficulties are structural and severely impact the credibility of Europeans to defend themselves or to engage militarily in the defence of their interests. The recently published European White Paper clearly highlights this challenge and identifies military mobility as a key capability priority to ensure Europeans are ready to defend themselves by 2030. To this end, a new joint communication by the European Commission and the European External Action Service (EEAS) is expected to be released in June to propose new measures.

One of the proposals should be to be the establishment of a European Strategic Mobility Agency, which would own transport assets and logistical equipment, thereby providing concrete facilitation of force movements across Europe.

Observation: Many initiatives launched, but not yet fully effective

At EU level, policies are being developed in both the community and intergovernmental spheres:

- Since 2021, the European Commission has managed a dedicated budget of €1.5 billion for funding dual-use transport infrastructure (both civilian and military). This fund is part of the Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) and is thus managed by DG MOVE in coordination with the EU Military Staff (EUMS), to ensure that projects address military needs (e.g. renovation of the rail terminal connected to the port of La Rochelle, or sections of the Rail Baltica in the Baltic States). All three project calls launched to date have fully utilised the available funding. However, the fund’s limitations are acknowledged, notably its focus solely on dual-use and not purely military infrastructure, which remains a critical need. Most Member States are calling for an increase in this allocation under the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF).

- In the intergovernmental sphere, two Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) projects address the issue. The first, simply titled “Military Mobility,” is led by the Netherlands and acts as a coordination forum for all European policies in this area, involving the Commission, the European Defence Agency (EDA), the EEAS, NATO, and several allied countries (including the US, Canada, Norway, and the UK). The second, “Network of Logistic Hubs in Support of Operations” (NetLogHubs), aims to consolidate a network of military logistics centres across Europe by listing logistical services (fuel, spare parts, accommodation, general supplies, etc.) available at European bases on a shared platform to facilitate movement and planning for armed forces.

- Capability development projects under PESCO will also directly contribute to military mobility in the coming decades. The “Future Mid-size Tactical Cargo” (FMTC) project, coordinated by France, seeks to define Europe’s future tactical airlift capability to replace CASA and C-130 aircraft. The “Strategic Air Transport for Outsized Cargo” (SATOC), led by Germany, is exploring a European solution for oversized strategic air transport, to eventually replace ageing Antonov aircraft currently used by several Allies. Both projects are supported by the European Defence Fund (EDF) for their initial studies.

- The EDA also supports Member States on capability matters and in harmonising border-crossing procedures, which are key to military mobility. For example, European countries still struggle to rapidly issue transit permission for foreign military movements by land or air. Other challenges involve differing regulations on the transport of dangerous goods. Most Member States have signed technical arrangements to harmonise these procedures, but implementation remains patchy across the EU.

- Overall, cooperation between the Commission and the Member States in this area is strong. Spanning both intergovernmental and community domains, an action plan on military mobility was in place for the 2018–2022 period, followed by a second for 2022–2026. These plans were accompanied by political “pledges” in 2018 and again in 2024, all recognising the need to make progress in the following areas: transport and storage infrastructure (including energy and its cybersecurity), mobility equipment and assets, border-crossing procedures (across all domains), and coordination and pooling of resources (notably with NATO).

Structural capability shortfalls are affecting European credibility

European armies are among the most deployed forces globally and have gained significant experience in mobility and logistics, both in terms of rapid deployment and sustained support. They nevertheless continue to face persistent obstacles to mobility, particularly within Europe:

- In the early phases of rapid deployment, strategic airlift capabilities are essential but remain insufficient. The “Strategic Airlift International Solution” (SALIS) contract allows some countries to access five ageing An-124 Antonov aircraft based in Leipzig – this fleet is increasingly vulnerable, especially as Antonov is a Ukrainian company under considerable strain. These aircraft are especially useful for transporting large volumes of equipment, vehicles, and helicopters far more quickly than land or sea routes. However, as such aircraft are not needed continuously, developing and acquiring these capabilities solely for military use in small national quantities is economically unsustainable.

- In subsequent phases, when support and supply of deployed forces is needed, there is also a capability gap in the transport of equipment – particularly trains and large roll-on/roll-off vessels. Armed forces today rely heavily on outsourcing, yet dependence on private operators can be problematic in times of conflict. Civilian assets could become targets, particularly when transporting military equipment, and companies may understandably reduce their operations due to risk (also deterring insurers and banks or driving up costs). In wartime, competition for deliveries between the military and civilian sectors would intensify, unless legal mechanisms such as requisitions or prioritisation were applied – which does not make military contracts more attractive to these companies.

Improving military mobility is also a matter of operational credibility and thus contributes to conventional deterrence. Europe’s current capabilities (including transport and storage infrastructure, especially energy-related) do not provide a credible basis for military engagement on European soil. Moreover, one of the key lessons from the war in Ukraine is the critical importance of logistics and resupply capabilities – potentially the main weakness of European forces in a major engagement[2].

The European White Paper places military mobility on par with other priorities of European rearmament

The joint White Paper by the European Commission and the EEAS, published on 19 March 2025, identifies military mobility as one of four missions through which the EU provides added value in the event of a major confrontation by 2030. It falls under two of the seven identified capability funding priorities: first, as part of infrastructure, and second under the category “Strategic enablers and protection of critical infrastructure,” including strategic transport, air-to-air refuelling, and operational energy infrastructure. Some additional points include:

- The White Paper affirms that military mobility contributes both to our preparedness and our deterrence.

- It is an area of effort that will also benefit the civilian sector (dual-use infrastructure).

- Four priority corridors are identified by the Commission, across all domains, as well as 500 “hotspots” requiring improvement. On energy transport, the White Paper calls on Member States and NATO to help complete the needs mapping.

- The corridors will be extended to Ukraine, to facilitate military assistance and ensure lasting security guarantees.

- The Commission plans to identify all EU legislation affecting military mobility (e.g. on the acquisition of stakes in critical infrastructure by potentially malicious actors) and propose revisions.

- The availability of specialised and dual-use assets is also highlighted.

- Infrastructure projects would benefit from more predictable EU financing.

- Lastly, military mobility is targeted under the SAFE[3] loan instrument.

The Commission and the EEAS are expected to release a joint communication on military mobility by the end of 2025 to propose new implementation actions.

Proposal to step up the gear: the creation of a European Strategic Mobility Agency (ESMA)

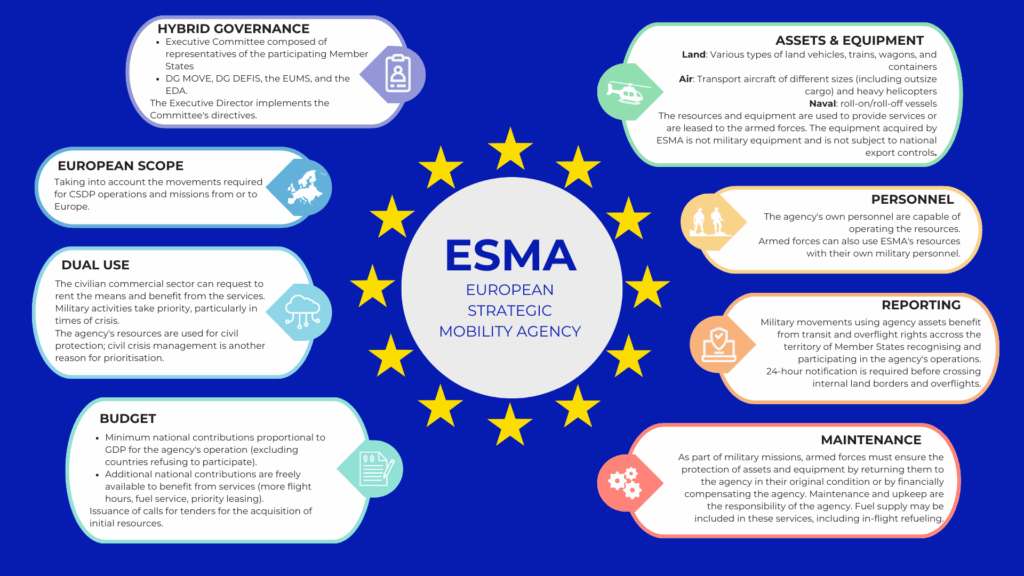

The agency would have its own assets and equipment to provide services or lease them to the armed forces. These assets and equipment would include various types of land vehicles, trains, wagons, and containers for land transport; transport aircraft of different sizes (including outsize cargo) for air transport; and roll-on/roll-off vessels, particularly for maritime routes.

The assets and services would be dual use: the civilian commercial sector could also request to lease the assets and benefit from the services. This dual-use model would ensure the agency’s economic sustainability. However, military activities would remain a priority, particularly in times of crisis. Moreover, civil crisis management could also justify prioritisation, and civil protection would be another area in which the agency’s assets could be employed.

Its legal status would be a challenge to address:

- In the case of an EU agency (like Frontex, for example), it can already possess (acquire and lease) its own assets. The legal difficulty would therefore lie more in its commercial activity alongside the services provided to the armed forces.

- An independent international public organisation, legally separate from the EU but closely linked to it, might therefore be preferable. This would also facilitate the agency’s use by non-member states wishing to associate with the project. However, the legal format to enable such an activity would need to be innovative.

- A possible solution could be a public-private partnership: the Member States and the Commission could create, alongside private companies, an entity capable of providing services to the armed forces on one hand and conducting commercial activity on the other (like the HeliDax model in France, but far more innovative on a European scale).

- Other innovative legal structures may also need to be considered, without requiring changes to the EU treaties.

Its governance would be hybrid, with an executive committee composed of representatives from participating Member States, the European Commission, the EU Military Staff, the European Defence Agency, and the participating companies.

Its budget would be composed of minimum national contributions proportionate to GDP to reach the agency’s viable minimum operating threshold (excluding countries opting out), with additional national contributions left to each state to access more services (such as more flight hours, fuel provision, or prioritised leasing).

The scope of the actions carried out by the armed forces using the agency’s assets would include European territory, as well as movements required for CSDP missions and operations to or from Europe.

The agency would also have its own personnel capable of operating the assets. However, the armed forces could also use them with their own military personnel.

For military missions, depending on the type of mission, the armed forces would be responsible for protecting the agency’s assets and returning them in their original condition, or compensating the agency financially otherwise.

Maintenance and operational readiness would be the responsibility of the agency. Fuel provision could also be included among the services, including aerial refuelling.

Military movements using the agency’s assets would benefit from transit and overflight rights across the territory of Member States recognising and participating in the agency’s operations.

The agency would require significant initial investment from Member States, with a build-up period spanning several years. Air assets would need to be based at airports, land assets along major logistical routes, and roll-on/roll-off vessels in key European ports.

Furthermore, the equipment acquired by the entity must not be classified as military matériel subject to national export controls. This question is particularly relevant to aircraft – using the example of SATOC (or A800M) must absolutely be an aircraft used in the commercial sector and should be among the assets acquired by the agency.

Conclusion

It is high time that military mobility and logistics were made a priority for European defence. The White Paper rises to this challenge. But implementation is key.

The creation of a European Strategic Mobility Agency could meet the needs of the armed forces by enabling greater agility and speed of movement, while benefiting from joint investment in shared capabilities. Moreover, it would facilitate the operationalisation of the Rapid Deployment Capacity and improve the effectiveness of all CSDP missions and operations. Above all, it would demonstrate the strength and added value of the European level in defence without infringing on national prerogatives. Lastly, it would reinforce Europe’s defence in this new era of contestation of European interests that we have entered.

The legal status of such an entity presents a challenge. Nonetheless, if it comes into being, it will demonstrate the relevance and necessity of deeper interconnection between the military and civilian worlds on the one hand, and between the public and private sectors on the other, to amplify our collective power in Europe.

[1] Member States and Allies broadly agree on the need for cooperation between the EU and NATO in this field, with non-member states also taking part in EU projects (such as PESCO), for example.

[2] Read for example: Ti, Ronald, and Christopher Kinsey. 2023. “Lessons from the Russo-Ukrainian Conflict: The Primacy of Logistics over Strategy.” Defence Studies 23 (3): 381–98. doi:10.1080/14702436.2023.2238613. Link.

[3] « Security Action for Europe (SAFE) through the reinforcement of European defence industry Instrument » which is a European Commission’s proposed regulation. Link.