Interviews

9 December 2024

Russia in the Post-Soviet Space: What Strategies of Influence?

2024 was marked by a significant number of decisive elections in countries formerly part of the USSR or within its sphere of influence, including Moldova, Georgia, and Romania. In each of these elections, “pro-Russian” parties performed well, and in some cases, massive fraud in their favour was reported. At the same time, Russia is striving to expand its sphere of influence towards countries in the so-called “Global South.”

What is Russia’s strategy of influence in Eastern Europe? How can the strong performance of pro-Russian candidates be explained? How is Moscow’s strategy unfolding on other continents? Insights from Lukas Aubin, research director at IRIS and a specialist in Russian geopolitics. He recently co-edited issue 135 of La Revue internationale et stratégique (RIS), dedicated to the post-Soviet space.

The pro-European parties of Moldova and Georgia, two former Soviet Republics, have accused Russia of interference in the recently held elections in both countries. What are these accusations based on? What is Russia’s strategy of influence in these states?

The accusations of Russian interference in the recent elections in Moldova and Georgia are based on several elements, often documented by international observers, local governments, or independent analyses. During the Georgian parliamentary elections on October 26, 2024, NGOs such as Transparency International denounced widespread and systemic fraud benefiting the pro-Russian party “Georgian Dream,” including ballot stuffing and voter intimidation. Similarly, regarding Georgia’s legislative elections, observers from the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) stated that the elections were “marred by inequalities among candidates, pressure, and tensions,” again favouring a pro-Kremlin party. While it is difficult to precisely identify who is behind these frauds, suspicion falls on Moscow. For example, Georgian President Salome Zourabichvili accused Russia of orchestrating “a special Russian operation, a hybrid war against the Georgian people.”

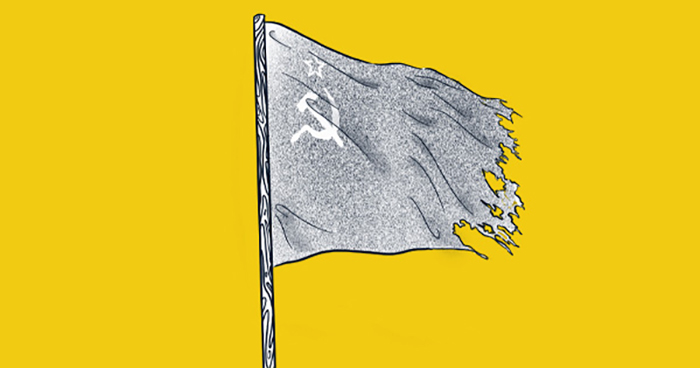

These accusations align with a Russian influence strategy that has been in place since the collapse of the USSR, intensified during Vladimir Putin’s era, aiming to maintain geopolitical control over these two former Soviet Republics, particularly in response to their aspirations to strengthen ties with the European Union (EU) and NATO. Broadly speaking, Russia considers the post-Soviet space its “near abroad,” over which it must maintain primary influence. The goal is not to reform the USSR but to preserve a “neo-imperial” influence over the former USSR. In other words, the dust from the fall of the Soviet Empire has not yet fully settled. Since Vladimir Putin came to power, and even more so since the “colour revolutions” in some post-Soviet countries in the mid-2000s, the Russian government has developed an arsenal of tools to spread its influence in the former USSR. This is what Mark Galeotti calls “the weaponization of everything.”

Thus, Russia uses controlled or influenced media to disseminate anti-Western narratives in Moldova and Georgia. These campaigns aim to weaken trust in pro-European parties and strengthen political forces aligned with Moscow. Russian media outlets, such as Sputnik and Russia Today (RT), regularly broadcast anti-European narratives in Moldova. They accuse the EU of wanting to exploit the country or claim that pro-European reforms will harm the economy and traditional values. Disinformation campaigns on digital platforms, particularly via social networks, spread narratives about alleged Western “moral decadence” or “interference” to undermine support for European integration. For instance, RT has been directly involved in supporting Moldovan pro-Russian oligarch Ilan Shor for several years with the Kremlin’s approval. From the perspective of public diplomacy and cultural influence, Russia uses organizations like Russkiy Mir (Russian World) to promote its language, culture, and historical narrative, particularly among Russian-speaking or Orthodox populations in Georgia and Moldova.

This multi-faceted influence strategy also relies on supporting pro-Russian political parties. The governments of Moldova and Georgia have accused Russia of directly or indirectly funding pro-Russian political parties and movements to influence electoral outcomes. Evidence of financial interventions, such as clandestine election campaign support, has even been presented. More broadly, Moscow funds or supports ultra-conservative and religious movements to counter progressive values perceived as Western. This includes campaigns against LGBTQIA+ rights or the promotion of a traditional societal model. The goal is to spread a narrative that is both anti-Western and conservative, aligning with the one propagated by Vladimir Putin.

Generally speaking, Russia has also been accused of launching cyberattacks against government institutions and critical infrastructure to create chaos before elections. For example, in 2021, ahead of Moldova’s parliamentary elections, cyberattacks attributed to Russian-linked groups targeted Moldovan institutions. These attacks aimed to cast doubt on electoral security and discredit pro-European authorities. These attacks include the dissemination of hacked documents to tarnish pro-European political figures.

To ensure its influence strategy in the “near abroad” is effective, the Russian government also relies on Russian-speaking populations—referred to by the Kremlin as “compatriots abroad”—present in these countries and on mobilizing ethnic or linguistic minorities. Thus, in Moldova, Russia relies on Russian-speaking populations and the separatist region of Transnistria to shape political dynamics, while in Georgia, Moscow exploits tensions surrounding the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia to exert constant pressure on the central government. For Moscow, leveraging frozen conflicts is a political strategy. Russia maintains troops in Transnistria (Moldova) and supports the separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia (Georgia). This enables Moscow to retain leverage over these countries, hinder their Euro-Atlantic aspirations, and foment internal tensions.

Finally, the Russian regime regularly uses economic and energy pressures. Russia leverages gas exports and economic sanctions as tools of coercion. For instance, it has reduced or cut off gas supplies to these countries at strategic moments. It also targets vital economic sectors, such as agricultural or wine trade, to punish pro-Western policies.

This arsenal of tools for disseminating Russian influence abroad primarily aims to dissuade Moldova and Georgia from joining NATO and, to a lesser extent, the EU, while indirectly preventing these states from drifting away from the Russian orbit. Naturally, the effects of this strategy are varied. In Georgia, Russia is currently experiencing a strong moment as its strategy yields results. Conversely, Moldova under Maia Sandu is cautiously leaning Westward, albeit in small steps.

Among the Eastern European NATO member countries, Slovakia and Hungary show a certain proximity to Moscow. Kremlin-aligned parties have also recently garnered very high scores in former East Germany and Romania. How can this renewed attraction to Russia in the post-Soviet space be explained?

For several years, some countries in Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet space have shown a renewed attraction to local pro-Russian political parties. However, it is often the rejection of certain aspects of the West that prevails over a genuine attraction to Russia. This phenomenon, though varied according to national contexts, can be explained by a combination of historical, economic, cultural, and geopolitical factors.

In countries like Hungary, Slovakia, or regions of former East Germany, segments of the population—usually those over 40—harbour a certain nostalgia for the Soviet era. While this period is often viewed negatively in the West, some may see it as a time of economic and social stability. This memory sometimes helps to temper criticism of Moscow. Additionally, Russian cultural influences—such as language, literature, or music—remain strong and can sometimes contribute to a favourable perception of Russia, or at least a form of nostalgia.

However, the attraction to pro-Russian parties is less about support for Moscow than a growing opposition to Western institutions, particularly the European Union and NATO. In countries like Hungary and Slovakia, political parties openly criticise the perceived interference of Brussels and the policies deemed belligerent by NATO, particularly regarding Ukraine. In response, Russia presents itself as a defender of national sovereignty and cultural identities, a narrative that resonates with eurosceptic nationalists.

Energy dependence also serves as a key lever of Russian influence. In Hungary, for example, imports of Russian gas and oil remain essential to the national economy, prompting the government to adopt a more conciliatory position toward Moscow. Moreover, Western sanctions against Russia have had side effects, such as rising energy prices or the loss of markets for certain local industries, reinforcing the discourse of pro-Russian parties. As we have seen, Russia also makes significant efforts to influence public opinion in these regions. The aim is to spread narratives that criticise Western policies while boosting the image of Moscow. These media platforms, active in local languages, are particularly present in Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, and Moldova. At the same time, direct or indirect support for eurosceptic or nationalist parties strengthens this dynamic. In former East Germany, the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) thus enjoys significant support in regions where nostalgia for the East German era remains strong.

Rejection of Western policies is often accompanied by opposition to the war in Ukraine. In Hungary, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán advocates for neutrality, criticising sanctions against Russia and calling for dialogue. These positions reinforce the image of Russia as an actor of stability, particularly among populations tired of the economic impacts of the conflict.

The rise and attractiveness of pro-Russian parties in these regions therefore rests on a balance between historical legacy, economic opportunities, criticisms of Western policies, and Russia’s proactive influence strategy. This renewed influence highlights Moscow’s ability to rely on local dynamics to maintain a significant presence in a polarised international context.

As the war continues, Europe seems to be increasingly polarising between pro-Russian and pro-Ukrainian parties, and more broadly, between anti- and pro-Western parties.

While Russia has pivoted towards the “Global South” and especially Asia since the war in Ukraine, how is its global influence strategy materialising?

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Russia has intensified its efforts to reposition its influence globally, particularly by turning towards the “Global South,” which includes Asia, Africa, Latin America, and parts of the Middle East. The BRICS summit in Kazan last October is one of the striking examples of this. The goal is clear: to unite what Moscow calls the “global majority” – that is, non-Western countries – to create a geopolitical, geoeconomic, and energy counterbalance to the West.

However, contrary to popular belief, this strategy did not begin on February 24, 2022, or with the annexation of Crimea in 2014. As early as the 1990s, Evgeny Primakov, then Foreign Minister and later Prime Minister, advocated the idea that in order to counter American hegemony, Russia should establish strong relationships with emerging powers like China and India. After an initial period of mistrust, Russian-Chinese relations intensified as border disputes between the two countries were resolved. The historic agreement of October 14, 2004, signed between Moscow and Beijing, marked the end of a centuries-old dispute by clearly defining their borders in the Far East. For the first time, the 4,250 kilometers of shared border were officially defined. From that point on, Vladimir Putin considered China a major strategic partner. In Russia, this is referred to as the “pivot to the East” (Povorot’ na Vostok, in Russian). Of course, this pivot has accelerated several times in response to the war in Ukraine and Western sanctions.

Today, this strategy relies on several key axes aimed at countering Russia’s growing isolation from Western powers. On the one hand, Russia has strengthened its relations with countries such as China, India, Iran, and Gulf states. Beijing is a key partner in this pivot, particularly in energy, trade, and geopolitical coordination. India, for its part, remains an important buyer of Russian arms and energy. The idea is to participate in the creation of alternative multilateral institutions such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) or the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) to promote a multipolar world and counter Western hegemony. This is supported by a combination of bilateral relations, media, trade, and military cooperation.

On the other hand, for this strategy to be effective, the Russian government relies on an anti-Western and pro-multipolar narrative. In other words, Russia exploits the resentment of many countries in the Global South towards former colonial powers and policies perceived as neo-colonial by Western countries. Moscow presents itself as a champion of national sovereignty and anti-imperialism. Thus, Russian state media such as RT and Sputnik disseminate content that challenges Western narratives, particularly regarding the war in Ukraine. These media are particularly active in Africa and Latin America, often publishing in local languages.

Therefore, Russia’s global influence strategy is part of a logic of diversifying its partnerships to bypass Western isolation. In short, Russia seeks to strengthen its role as a key player in a multipolar world while trying to divide the West. However, and importantly, it is currently difficult to assess the long-term effects of this strategy. Beyond spectacular announcements such as the BRICS summit, few concrete and impactful decisions have been made so far in a coordinated manner by emerging countries or the “global majority.” Like the world, the non-Western space remains more multipolar than unified and cohesive.