Interviews / Energy and Raw Materials

12 May 2025

Geopolitics of the Abyss: Power, Metals and Global Fractures

The United States’ unilateral initiative on deep-sea mining weakens the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and challenges the multilateral framework. Access to critical metals, essential to the energy transition, has become a strategic issue, as demonstrated by the pressure exerted by Washington on Greenland, Ukraine and the seabed. This dynamic highlights the current limitations of collective governance over global commons and marks the beginning of a new era in the global geopolitics of raw materials. An update with Emmanuel Hache, Director of Research at IRIS, and Romane Lucq, international strategy analyst specialising in maritime issues.

What geopolitical implications do the United States’ unilateral initiatives have for the legitimacy of the ISA and the balance of the international seabed regime?

The latest session of the ISA Council, held from 18 to 29 March 2025, was expected to move towards the adoption of a mining code to govern the commercial exploitation of mineral resources located beyond national jurisdictions. However, the number and complexity of the issues to be resolved – environmental safeguards, benefit-sharing mechanisms, licensing procedures, liability in case of damage, etc. – clearly showed that no compromise could be reached within the originally envisaged timeframe. It was in this context of regulatory deadlock that, on the final day of negotiations, The Metals Company (TMC) – a Canadian pioneer in the sector and the main advocate of a swift move to the exploitation phase – announced its intention to apply directly to the US authorities for an exploitation licence, relying on a 1980 national law, the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act. This statement immediately provoked strong reactions: more than 40 states took the floor to express concern over this circumvention of the multilateral process and its implications for international seabed governance.

A few weeks later, on 24 April 2025, Donald Trump took a further step by signing a presidential executive order entitled Unleashing America’s Offshore Critical Minerals and Resources. This text instructs federal agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), to accelerate the processing of permit applications for the exploitation of mineral resources in the high seas, whether within US jurisdiction or beyond. The stated objective is to guarantee the United States access to the critical metals needed for the energy transition, by supporting the emergence of a deep-sea mining industrial sector. Shortly afterwards, on 29 April 2025, TMC USA – the American subsidiary of TMC – officially submitted to NOAA a commercial licence application for the exploitation of polymetallic nodules in a 25,160 km² area in the Clarion-Clipperton abyssal plain, as well as additional exploration licences.

These initiatives mark a geopolitical turning point, in that they constitute an explicit bypass of the UN framework based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). By operating outside the established legal framework and disregarding the authority of the ISA, the United States undermines the founding principles of the multilateral regime set up to regulate the fair and responsible use of high-seas mineral resources. This deliberate circumvention of the collective mechanism, in favour of a reactivated national law serving strategic purposes, challenges the very principle of the common heritage of mankind, which underpins the normative basis for international seabed mineral resources. Moreover, by asserting direct and autonomous access to deep-sea resources, Washington sets a precedent likely to be followed by other powers with sufficient industrial, technological and financial capacities, which may be tempted to invoke their own national legislation to justify early exploitation, thereby contributing to a growing fragmentation of the international legal framework. Furthermore, this strategy of fait accompli weakens the room for manoeuvre of states and delegations engaged in building a compromise within the ISA. By reducing the scope for negotiation, it exacerbates tensions between those advocating a precautionary pause and those pushing for a rapid move to the exploitation phase. This divide, now accentuated by the American stance, further undermines the prospects for a multilateral mining code.

How can we explain the growing divergences between states on deep-sea mining, and what do they reveal about broader geopolitical fractures in the governance of global commons?

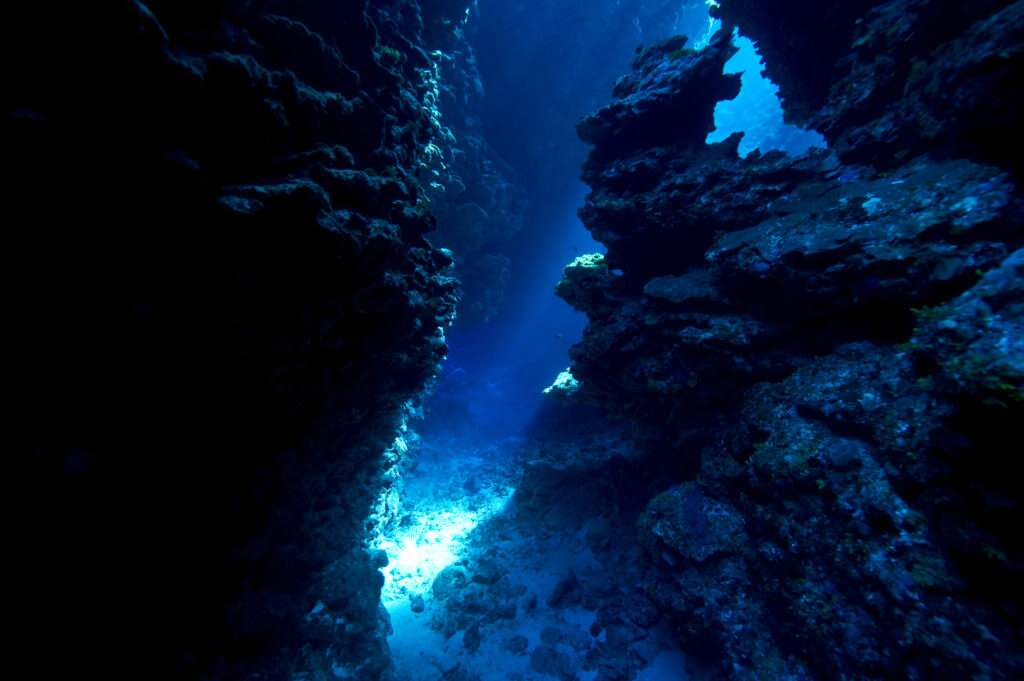

The polarisation of state positions is primarily due to scientific uncertainty surrounding the deep sea. This is a largely unexplored area – it is estimated that only 25% of the seabed has been accurately mapped – home to unknown biodiversity, whose ecosystem dynamics and interactions with the rest of the marine environment are still poorly understood. In such a context, moving to exploitation means taking a position on an acceptable level of uncertainty, the reversibility of impacts, and the very nature of the relationship between humanity and the marine environment. While scientists warn of major harm to ecosystem balances – the disappearance of yet unknown species, long-term disruption to abyssal fauna and flora, and the spread of particles likely to degrade marine environments – the legal frameworks to prevent or regulate these impacts remain inadequate. The triggering of the “two-year rule” by Nauru in 2021 – which theoretically allows exploitation to begin even without finalised rules – increased the pressure on negotiations, deepening divisions between states in favour of a swift move to exploitation and those who believe that, in the absence of robust knowledge, the precautionary principle must prevail.

These divisions reveal deeply divergent state strategies. On one side, a group of countries – China, Russia, India, etc. – is investing in exploration technologies and seeks to secure direct access to these resources, particularly in view of increasing competition over critical metals, seeing the deep sea as a lever for technological sovereignty and economic power. Alongside them, several island states – Nauru, Tonga – have sponsored mining companies, often within a national development logic based on rents from the blue economy. Conversely, a growing coalition of states – including France, Germany, Chile, Costa Rica and Vanuatu – is calling for a moratorium. These countries point to the lack of scientific evidence demonstrating the harmlessness of exploitation, as well as the irreversibility of potential harm to biodiversity. Moreover, some also highlight the inconsistency of promoting such activity at a time when the international community is adopting conservation targets of 30% of the ocean by 2030 (Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework) and celebrating the international treaty for the protection of the high seas and marine biodiversity (BBNJ).

But beyond national strategies, what is at stake is more fundamental: the international system’s inability to ensure credible, fair and legitimate governance of what is supposed to be part of the common heritage of mankind. This concept, at the heart of UNCLOS, aims to make international seabed mineral resources a shared good, collectively managed in the interest of all, and especially of countries lacking the technical capacity to access them. Yet, the practical modalities of this management and benefit-sharing remain largely undefined, and the ISA, which is meant to embody this collective framework, sees its legitimacy challenged both by those who deem its governance too slow and those who criticise its openness to industrial interests.

As a result, the growing tensions surrounding deep-sea mining are not simply a matter of differing legal interpretations or technical assessments, but reflect a deeper clash between competing visions for the future of global commons, exposing the structural blind spots of a multilateralism in crisis in the face of contemporary geopolitical realignments. The case of the seabed sharply illustrates the tensions between the universal ambitions of international law and the reality of current power relations. As resource-related stakes shift towards extraterritorial spaces – cyberspace, low Earth orbit, outer space or oceanic abyssal zones – the international community’s capacity to produce common, binding and equitable norms is eroding. The governance of global commons is increasingly being challenged by logics of appropriation, strategic anticipation and legal circumvention.

To what extent are the metals found in the seabed truly strategic for the energy transition, and what alternatives could be considered to limit dependency on their exploitation?

The low-carbon and digital transition, as well as the military sector, rely on a growing demand for metals. The metal-intensive nature of these current dynamics has notably been highlighted by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which estimated in 2024 that a carbon-neutral scenario would multiply global demand for copper by 1.5, for cobalt, nickel and rare earths by 2, for graphite by around 4, and for lithium by 9 — materials found in abundance in the seabed. Their exploitation thus appears, for some actors, as a key strategic lever in the reconfiguration of metal supply chains. It could notably bypass traditional geopolitical logics based on the concentration of terrestrial resources and the prerogatives of states. Today, a significant share of global metal production is located in areas marked by high political instability (Democratic Republic of Congo, etc.), or by economic strategies favouring power relations, with many threats of restrictions or embargoes, as seen in China or Indonesia. These dynamics expose value chains to disruption risks and strategic dependency. Moreover, the geopolitical interest in deep-sea resources is not limited to the abundance of strategic metals such as manganese, copper, nickel, cobalt or certain rare earths (Table 1), but also in their significantly higher concentration in these environments than in terrestrial deposits.

| Terrestrial reserves (kt) | Polymetallic nodules resources in the CCZ (kt) | Nodules/Reserves Ratio | |

| Cobalt Copper Lithium Manganese Nickel Rare earths | 11 000 1 000 000 28 000 1 900 000 130 000 110 000 | 44 000 226 000 2 800 5 992 000 274 000 15 100 | 300 % 22,6 % 10 % 215,4 % 110 % 13,7 % |

Sources: USGS; IEA; Hein et al. 2013[2].

Their particular geographical situation is also a factor: a large proportion of these deposits lie beyond national jurisdictions, in international zones, raising crucial issues of governance, sovereignty and strategic competition between powers. Lastly, proponents see deep-sea mining as a way to avoid the issue of local acceptance, often problematic near major terrestrial mining sites.

However, alongside these logics, developing the seabed is a major source of ecological uncertainty. The precautionary principle must apply because we do not yet understand these vital ecosystems. Furthermore, even from a purely economic perspective, there is no serious study proving the viability of this type of exploitation. Other strategies must therefore be explored, such as improving recycling or embracing material sobriety, before exploiting one of humanity’s last remaining commons.

Greenland, Ukraine and now the seabed: are the United States launching a war for critical metals?

As early as 2017 during Donald Trump’s first term, the issue of critical metals was described as an extraordinary threat to national security, with underlying concerns over dependence on Beijing. China, along with Canada, is one of the two main suppliers of critical metals to a country that remains 100% dependent on ten strategic metals and over 50% dependent on 31 of them. Critical metals are thus a key to understanding the United States’ international strategy. And the playing fields for the Trump administration on this issue are many: Greenland, Ukraine and the seabed. All of them, to varying degrees, follow a sacrificial logic: sacrificing a territory to secure strategic independence. Trump’s controversial attempts in 2019 to acquire Greenland – whether through negotiation or coercion – illustrate the growing perception of this territory as highly strategic due to its mineral potential (copper, gold, graphite, molybdenum and nickel). The potential presence of rare earths – Greenland is estimated to hold around 1.7% of the world’s reserves according to the US Geological Survey (USGS) – reinforces these ambitions. The rare earths market, essential for producing permanent magnets used in electric motors and some wind turbines, is dominated by China, which extracts about 69% and refines over 90%. Annexing Greenland or exploiting the seabed represents the US solution to reducing dependence on China, which holds a genuine strategic lever in this market. This drive to control resources also goes hand in hand with a desire to limit access for its geopolitical rivals, notably China, the European Union (EU) and Russia. US pressure to sign an agreement with Ukraine on critical materials follows the same logic. Ukraine is believed to hold significant mining potential – titanium, lithium, graphite, rare earths, zirconium – which may represent around 5% of global resources. Even though, here too, the uncertainties are considerable – geological data is outdated and mostly from the Soviet era, and the economic profitability of these deposits is highly uncertain – the United States is keen to demonstrate its ability to secure its supplies using all its influence or brute force. Yet the race for strategic resources is not confined to these territories. The United States is also active in Africa, and this renewed presence comes at a time when China and the Gulf countries, especially the UAE and Saudi Arabia, have invested heavily in the African mining sector, with diversified strategies combining investment, infrastructure and diplomatic influence.

In this context, global geopolitics is increasingly organised around metallic issues and the development of mining networks – genuine webs combining economic, diplomatic and military agreements. We are witnessing the forceful return of a “geopolitics of raw materials”, reminding us that energy sovereignty necessarily involves both industrial and mineral reconquest.

[1] Emmanuel Hache, Émilie Normand, and Candice Roche, “Exploiting the Seabed: A New Geopolitical Frontier?”, La Revue internationale et stratégique 136, no. 4 (Winter 2024): 173–183.

[2] James R. Hein, Kathryn Mizell, Andrea Koschinsky et Thomas A. Conrad, “Deep-Ocean Mineral Deposits as a Source of Critical Metals for High- and Green-Technology Applications: Comparison with Land-Based Resources », Ore Geology Reviews 51 (2013) : 1–14.