Interviews / Asia-Pacific

28 October 2025

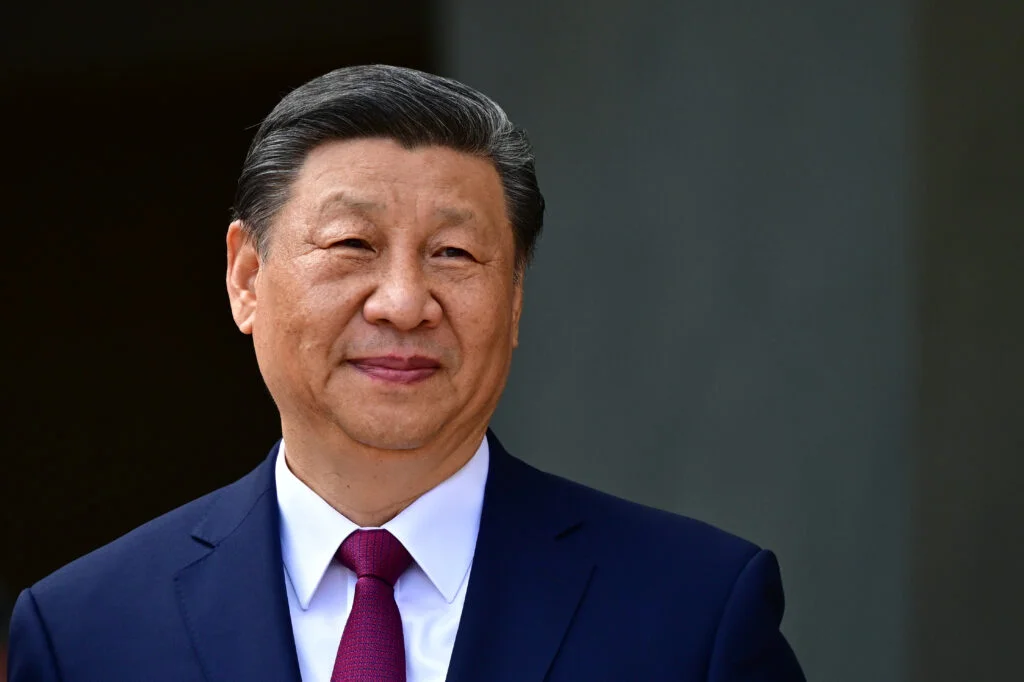

China’s New Five-Year Plan: Between Strategic Autonomy and Economic Recentring

Held in Beijing from 20 to 23 October, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) symposium outlined the main directions of the upcoming Five-Year Plan. During this closed-door meeting between leaders and experts, China’s political, economic, and military priorities appeared to converge under the guiding principles of strategic autonomy and technological sovereignty, in a context of growing rivalry with the United States. In what context did this symposium take place? Between economic recentering, military ambition, and the diplomacy of rare earths, what long-term domestic objectives does China appear to be pursuing, and what might be their international consequences? Insights from Emmanuel Lincot, Director of Research at IRIS and Co-Head of the Asia-Pacific Programme.

In what context did the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) symposium announcing the next Five-Year Plan take place, and what challenges does China face?

It is worth recalling that this symposium took place in Beijing between 20 and 23 October. Sign of the times: sixty-one senior officials were absent. Were they purged like the nine high-ranking officers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)? In any case, the symposium took place in a rather tense political climate and amid heightened frictions with the United States, marked by a significant tightening of control over the CCP’s senior hierarchy at the initiative of Xi Jinping. Among the key takeaways from the meeting was the emphasis on self-sufficiency in high technology. China must now return to a distinctly Maoist practice of relying solely on its own forces. This means becoming far less dependent on the outside world—and particularly on the United States—for artificial intelligence and the mastery of microprocessors. Finally, the Chinese leader urged the army to be ready for a potential military operation against Taiwan in 2027, a date that coincides with the centenary of the PLA’s founding. This does not necessarily imply that an offensive is imminent, but it clearly signals a desire to be capable of intimidating the United States.

What are the economic, technological, and industrial prospects outlined in this plan?

We can expect an even stronger focus on industrial autonomy. While China still depends on external sources for the supply of materials such as nickel and cobalt, it will need to reinvent itself and find a range of alternatives to make up for its shortcomings. The government will mainly encourage greater synergy between the public and private sectors to catch up in the field of advanced technologies. This is where Xi Jinping’s credibility is most at stake. China’s progress in manufacturing next-generation microprocessors will have repercussions across many sectors—from communications and anti-submarine warfare systems to drone technologies and aerospace innovation. Strategically, this means a partial but tangible inward turn for China. The country is preparing for the worst—namely, a confrontation with the West.

Earlier this month, Beijing announced new restrictions on the export of rare earths. To what extent does this decision fit into the framework of Sino-American rivalry, and what could be its consequences for other states, particularly the European Union?

It should be noted that licences for rare earth exploitation are extremely restrictive, typically renewed—or not—every six months. This naturally prevents industrial players from planning in the long term. As is well known, China, which holds a monopoly on the extraction of these resources worldwide, uses rare earths as a tool of blackmail and leverage against the West, notably against Donald Trump, even though a compromise—or rather, a temporary reprieve—appears to have been reached between the Americans and the Chinese ahead of the meeting scheduled between the two leaders on 30 October. Buying time has become crucial for both sides. For Western countries in particular, it is now essential to rebuild their rare earth supply chains to reduce their dependency on China. It is worth recalling that France, thirty years ago, held the global monopoly on rare earth extraction. It was only from the 2000s onwards that Paris relocated its production to China for reasons of both cost and environmental considerations. In short, Europeans will not be spared by this escalation of tensions with China. They will have no choice but to exercise both patience and strategy in adapting to the challenges of the moment.