Interviews / Asia-Pacific

12 September 2025

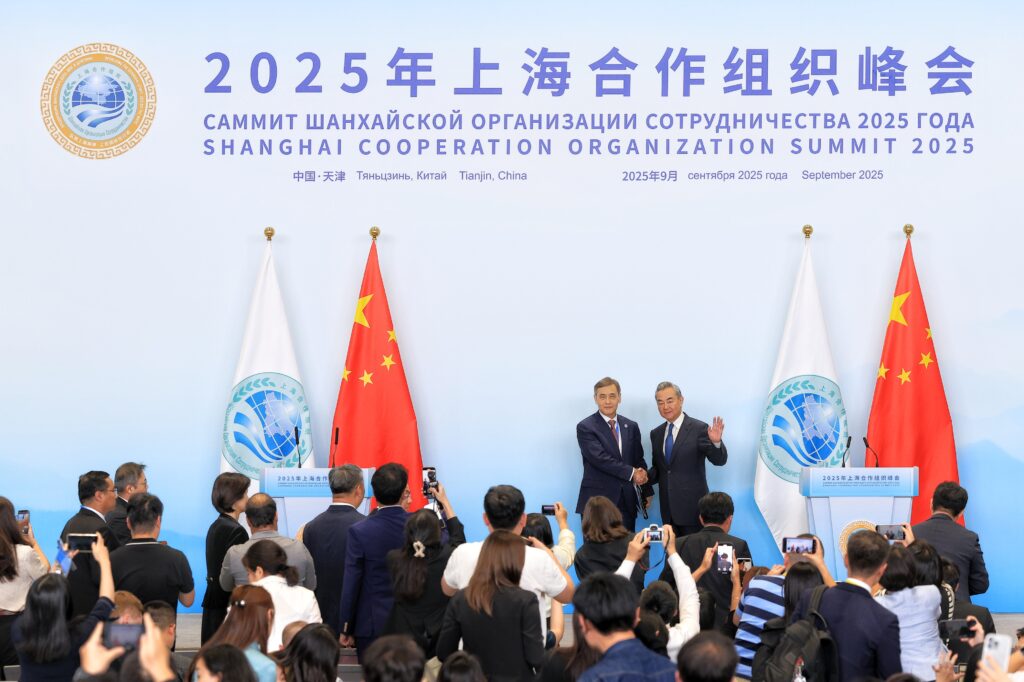

25th SCO Summit: Beijing at the Centre of a New World Order?

The 25th summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) was held on 31 August and 1 September in Tianjin, China. Bringing together around twenty Eurasian heads of state and government, this summit took place in an international context marked by a questioning of the concept of the “Western world” under Trump II’s foreign policy and the redefinition of a new world order. What lessons can be drawn from this summit? What does it reveal about Beijing’s strategic positioning on the international stage? What was the significance, for Beijing, of the Indian Prime Minister’s attendance? Emmanuel Lincot, Director of Research at IRIS and co-head of the Asia-Pacific Programme, shares his insights.

What were the stakes of this summit and what conclusions can be drawn from it?

This summit had all the hallmarks of a circumstantial gathering of friends, notably between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin (who were meeting for the sixtieth time). Their leitmotif is “peace” and a “new, fairer international order”. Yet how can one aspire to a new international order if it is not based on the rule of law? There is an institution for that: the United Nations. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation offers nothing other than arbitrariness and intimidation through the use of force. However, unlike the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) created by the Russians in 2002 or the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the SCO has no power projection capability. The Tianjin summit was intended, at a rhetorical level, to pose a threat to democracies — not only those of the Old Continent or the Americas, but also Asian democracies — in a very hackneyed fashion rooted in Carl Schmitt’s friend–enemy distinction. Yet it would require the Organisation to at least share some consensus among its members. Can one seriously imagine Pakistanis and Indians reconciling under its aegis after their skirmishes in Kashmir last April? Certainly not. Although the Russians remain attached to the idea of a community of shared interests — dating back to when Yevgeny Primakov, then Foreign Minister of the nascent Russian Federation, floated the project of a tripolar order shared between Moscow, Beijing and New Delhi — it is obviously utopian. Even if Narendra Modi seemed to play along with amicable gestures, this staging mainly served to express his anger at the sanctions imposed on India by Donald Trump. Two leaders, in terms of image, benefited from this summit: Vladimir Putin, who thereby enhances his international stature just weeks after his meeting with Donald Trump in Anchorage, and Iranian President Masoud Pezechkian, who is emerging from isolation after Israeli and American air strikes against his country. Finally, Xi Jinping confirmed his return to the national and global stage, while his absence from the BRICS summit and Politburo decisions sidelining him had fuelled widespread speculation about his health or even his possible removal from power.

This summit marked Narendra Modi’s return to Chinese soil for the first time since the Sino-Indian border conflict in the Galwan Valley in 2020. What does this meeting say about the evolving balance of power between the two Asian giants, particularly from China’s perspective? Can it be seen as a strategic strengthening of the SCO?

China’s goal is to anchor India to the Belt and Road Initiative, which New Delhi has rejected since its launch in 2013 for a simple reason: trade flows are asymmetrical, and Indian participation would only widen this gap. It is also, for Chinese diplomacy, about drawing India into its orbit with Moscow’s support, in order to weaken the Indo-Pacific. Can it succeed? Unlikely, given the many sticking points between the two countries: their border dispute, the Tibetan issue, the construction of the Brahmaputra dam, and China’s support for Pakistan. Moreover, Narendra Modi retains the traumatic memory of India’s military defeat in 1962. Since then, for the majority of Indians, the enemy is China. It is hard to imagine him going against such a widely held sentiment.

A few days after this summit, Beijing hosted the commemorations of the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War on 3 September, attended by Vladimir Putin and Kim Jong-un. What does this event reveal about China’s strategic posture and diplomatic affinities?

It is a way for the Chinese regime to recall the country’s contribution to the Second World War effort, with its twenty million deaths. No one disputes this, although it is striking to see the Communist Party claiming this victory in East Asia when in 1945 it was the Republic of China and the Kuomintang that secured Japan’s surrender. This revisionism is part of the narrative promoted by the regime. The 3 September parade was also an opportunity for the regime to showcase new military equipment, including hypersonic missiles and laser anti-aircraft batteries capable of shooting down enemy satellites. This military display, along with Xi Jinping’s posture, projected the image of an orderly, serious and determined society — in stark contrast, certainly, to the image projected by Donald Trump and the United States to the rest of the world. The presence of Kim Jong-un was a diplomatic success for the North Korean leader. More implicitly, for the Chinese, his presence served as a message to the Russians. The signing of a mutual assistance pact between Pyongyang and Moscow in June 2024 had been rather poorly received in Beijing. Xi Jinping is now reminding everyone that he is the master of clocks and that nothing will happen without taking Beijing’s position into account.