Interviews / Energy and Raw Materials

11 June 2024

Rare Earth Deposit Discovered in Norway: Good News for European Mineral Sovereignty?

A few days ago, 8.8 million tonnes of rare earth elements were discovered in south-eastern Norway. These chemical elements, essential for the low-carbon, ecological, and digital transition, could significantly reshape the landscape of European mineral autonomy and security, especially given that China currently accounts for nearly 69% of global mining production, leaving the European Union heavily dependent on external supplies.

What impact might this discovery have on the global rare earth market? How can the European continent benefit from it? Insights provided by Emmanuel Hache, research director at IRIS and a specialist in energy foresight and the economics of natural resources (energy and metals).

The Norwegian mining company Rare Earths Norway (“REN”) has announced the discovery of the largest rare earth deposit in mainland Europe, located in Norway. What are rare earth elements, and what does this discovery signify?

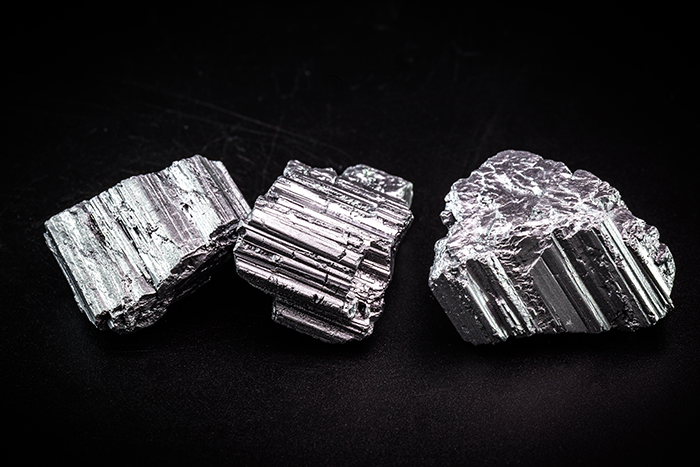

Rare earth elements refer to a group of 17 chemical elements (Scandium, Yttrium, Lanthanum, Cerium, Praseodymium, Neodymium, Promethium, Samarium, Europium, Gadolinium, Terbium, Dysprosium, Holmium, Erbium, Thulium, Ytterbium, and Lutetium). Contrary to their name, they are not rarer than other commonly used metals. At the current production rate (350,000 tonnes) and considering global reserves (110 million tonnes), the world has approximately 315 years’ worth of rare earth consumption ahead. Rare earths, therefore, are not critical from a geological standpoint.

The two main challenges in the rare earth market remain their environmental impact and the concentration of market players, particularly in China. The rare earth market is relatively narrow compared to the 22 million tonnes of the copper market, and price and transaction transparency remain low. Despite these weaknesses, rare earth elements are rightly regarded as essential “vitamins” for the global economy and the two ongoing transitions: the low-carbon and digital transitions. They have gradually become critical components in various advanced industries, especially in the military sector and low-carbon technologies.

Rare earths are particularly prominent in permanent magnets used in certain wind turbine rotors and electric vehicle motors, which already account for nearly 55% of rare earth usage. Contrary to popular belief, there are no rare earths in batteries. Their exceptional properties – impressive thermal stability, high electrical conductivity, and strong magnetism – have enabled significant advancements in technological performance while reducing material consumption.

The discovery made by REN follows the one reported in January 2023 by the Swedish mining group LKAB. The latter announced the identification of a deposit containing over one million tonnes of metals, including rare earths, in Swedish Lapland, representing about 1% of global reserves.

Could this discovery reshape the global rare earth market?

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) estimates global rare earth production at approximately 350,000 tonnes in 2023, compared to 300,000 tonnes in 2022—an increase of over 15%, reflecting the growing demand for these “vitamins” of the ongoing transitions. China is the leading producer, accounting for nearly 69% of global mining production, followed by the United States (12%), Myanmar (11%), Australia (5%), and Thailand (2%). Other countries, such as India, Russia, and Vietnam, also contribute to production.

Examining the distribution of global reserves provides further insights into the market. While China holds 40% of global reserves, Brazil and Vietnam each possess about 20%, with additional reserves found in countries like the United States, Australia, Canada, Greenland, Russia, South Africa, and Tanzania. A simple calculation comparing reserves in OECD and non-OECD countries reveals a stark contrast: OECD countries hold only 7.5% of global reserves, while non-OECD countries account for 92.5%. Among OECD nations, reserves are limited to Australia, Canada, the United States, and Greenland.

The scale of the Norwegian discovery—approximately 8.8 million tonnes of rare earths, equating to 1.5 million tonnes of permanent magnets used in electric vehicles and wind turbines—represents a significant asset for Europe. The rare earth market is among the most concentrated of all low-carbon transition metal markets. China’s dominance extends not only to mining but also to refining and separation, where it controls about 88% of global output.

Since the mid-1980s, China has strategically built its advantage in this sector. However, it is worth noting that Western countries significantly contributed to this development. Before the 1990s, the United States was the world’s leading rare earth producer, and until the mid-1980s, France—through Rhône-Poulenc—was one of the two global leaders in rare earth purification, holding nearly 50% of the market.

The quote attributed to Deng Xiaoping, “The Middle East has oil, China has rare earths,” encapsulates China’s mineral strategy as a central pillar of its international strategy. It also highlights the lack of strategic foresight by OECD countries, which chose to outsource the environmental impacts of their consumption rather than prioritise long-term supply security.

Is this good news for Europe and the region’s mineral sovereignty?

In September 2022, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, stated in her State of the Union address: “Lithium and rare earths will soon be more important than oil and gas. Our demand for rare earths alone will increase fivefold by 2030 […] The only problem is that currently, one single country controls almost the entire market.” This declaration underscores the urgency of establishing a European strategy for critical materials, as the continent remains over 98% dependent on external sources for its supplies.

The adoption of the European Regulation on Critical Raw Materials in April 2024 reflects this need. The regulation sets ambitious targets: 10% of European consumption must come from extraction within the EU, 40% from European refining, and measures are introduced to reduce dependency on a single country, while promoting recycling. However, despite these goals, discovery does not guarantee production in the short term.

In mining, timelines rarely align with the immediacy of the low-carbon transition. In the case of rare earths, environmental impacts must also be minimised to ensure public acceptance of mining projects. REN estimates a total investment of 10 billion Norwegian kroner (approximately €870 million) for the first phase of mining production, expected to start by 2030. This could eventually meet 10% of Europe’s consumption.

Yet, these investment requirements face uncertainties, including opposition to mining activities. In its May 2024 report, the International Energy Agency (IEA) highlights that demand for rare earth permanent magnets is expected to double by 2050 under climate scenarios aligned with the Paris Agreement.

Thus, while increased production is critical, it will not suffice in the short term. Other key measures, such as recycling and reducing usage, must also be developed and prioritised to ensure long-term sustainability and supply security.